Researchers pump programmed scents to make virtual reality users feel more present

While Capcom's Resident Evil 7 may already be terrifying in virtual reality, adding smells — ranging from a leafy forest to rotting flesh — really pushes things to a new level, researchers have found.

Putting volunteers into the virtual reality world of Capcom's zombie-filled Resident Evil 7, researchers have found that smells — particularly unpleasant ones — have a measurable effect on user presence, in a study which could prove important for future VR training systems.

This article was discussed in our Next Byte podcast.

The full article will continue below.

While it’s far from the first time the technology has tried to break into the mainstream, virtual reality is currently enjoying a renaissance for everything from training and telerobotics to entertainment — aided, in no small way, by the steady march of technology improving both the hardware and the underlying software.

Today’s virtual reality systems, however, concentrate almost exclusively on sight and sound, with a much smaller number attempting to leverage the user’s sense of touch. Even there, a big sense is left unused: Smell.

A team of scientists at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) and the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, aim to address that with proof that programmable scents, combined with off-the-shelf virtual reality hardware and software, can enhance a user’s sense of presence in the virtual world.

Smell-o-vision

The team set about building an experimental system designed to determine whether being able to smell, rather than just see, a virtual environment would engage users more deeply. The environment in question: Capcom’s survival horror Resident Evil 7, running on a PlayStation 4 games console with a PlayStation VR virtual reality headset.

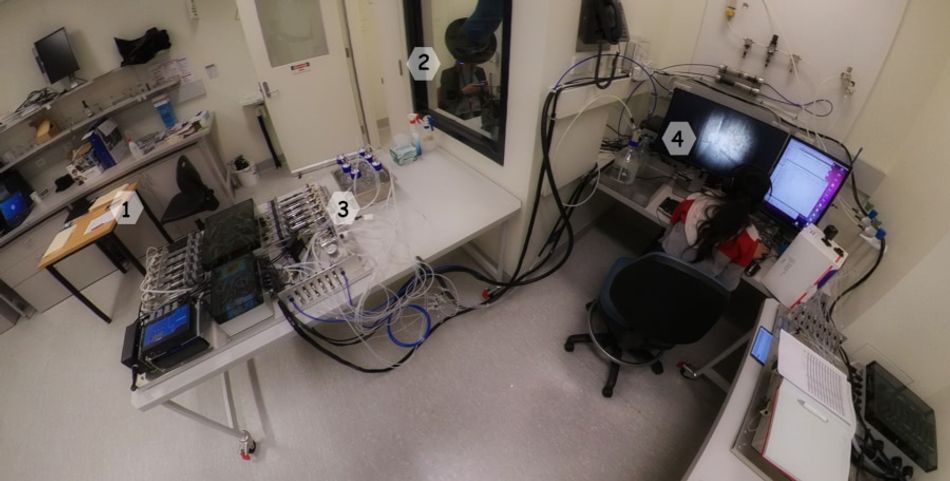

For the smells, the olfactometer portion of a custom-built simultaneous gustometer olfactometer (SGO), created for an earlier study, was employed. Featuring six computer-controlled mass-flow controls linked to the air flow through six glass saturators, the olfactometer can pump varying concentrations and mixtures of scents through a tube to the user’s nose.

Not all of the odors were ones you’d volunteer to smell under normal conditions. While the first odor, a green leafy scent dubbed “forest,” would be pleasant enough, and the “smoke” odor — produced by an off-the-shelf liquid mesquite smoke designed for barbecues — at least tolerable, the “dank” odor would be less palatable, while the “rotten” odor delivers exactly what it promises.

There’s a reason behind the selection of smells, though, and it ties in to the reason for using a zombie-themed survival horror game as the virtual environment. Previous studies, the team notes, had found that unpleasant odors had a measurably higher effect on the user’s sense of presence — and that odors matched to the virtual environment were more readily perceived. In other words: A surprise decapitated head which smells rotten should have a stronger impact than one which smells of flowers, or replacing the head with a bouquet of perfumed roses.

Smells like you’re really there

The experiment saw 22 participants placed in a walk-through game section which didn’t involve immediate peril, the use of weapons, or the appearance of enemies. First, they started next to a vehicle before walking through a forest; soon, the forest gave way to swamp. A disturbing sculpture gave off a rotten smell, while a fire offered the aroma of smoke. A kitchen revealed rotten food, which prepared the participants for a journey through dank water to find a surprise head floating next to them.

Of the 22 participants, 11 were also fitted with a wearable designed to track their physiological responses. Regardless of which group a participant was in, they were asked to complete questionnaires to determine their responses to the standard and smell-enhanced versions of the game.

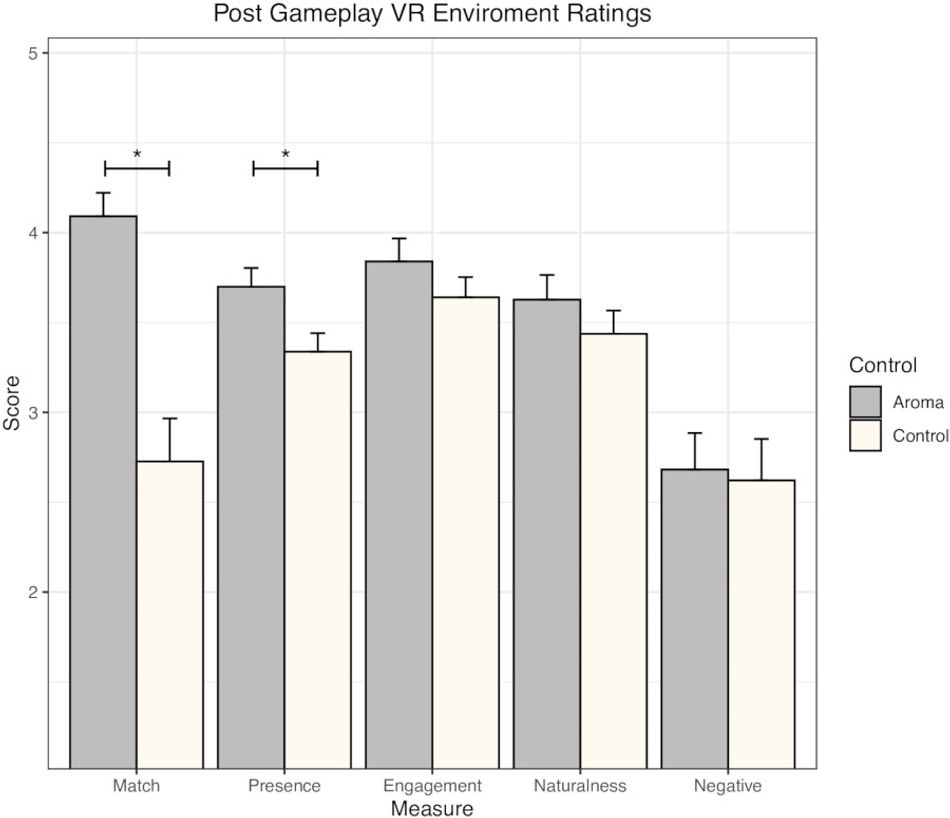

The results show promise. Participants generally reported an increased sense of spatial presence — the feeling of actually being present in the game world — when playing with the smells available. Interestingly, participants also appeared to exhibit heightened anxiety — though other emotional states did not appear to be affected. These reports were backed by data from the wearable sensors, finding increased heart rate and body temperature in the presence of odor and a significant decrease in electrodermal activity (EDA).

“While the game was a useful test bed for more ‘extreme’ smells,” the team notes, “we believe the findings from this study demonstrate that the use of smells in virtual environments should be serious considered for situations where presence and realism are critical [such as] virtual training environments for emergency services (fire fighting for example), military personnel, hazardous chemical response teams,” as well as virtual reality exposure therapy.

The team further suggests that the results are strong enough to support the development of commercial odor-delivery devices for integration into virtual reality hardware in the future, though a number of difficulties are noted — including the size of the hardware required and the cost of development, both of which suggest the technology would find a home in “larger-scale training simulations, gallery, and theme-park installations” long before anyone will be connected a programmable olfactometer to their PlayStations.

The team’s work has been published in the journal PLoS ONE under open-access terms.

Reference

Nicholas S. Archer, Andrew Bluff, Andrew Eddy, Chreshall K. Nikhil, Nick Hazell, Damian Frank, and Andrew Johnston: Odour enhances the sense of presence in a virtual reality environment, PLoS ONE 17(3). DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0265039.