Naturalis Biodiversity Center: Prehistoric prints, cutting-edge technology

In 2013, a team of paleontologists from the the Netherlands' national natural history museum, Naturalis Biodiversity Center travelled to Montana to excavate the skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex.

In 2013, a team of paleontologists from the the Netherlands' national natural history museum, Naturalis Biodiversity Center travelled to Montana to excavate the skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex. Leading the team was Prof. Dr. Anne S. Schulp, Researcher of Vertebrate Paleontology at Naturalis and Professor of Vertebrate Paleontology at Utrecht University. He was thrilled: The find was incredible. The skeleton was covered by a three-meter-thick layer of sand and had been remarkably well-preserved. It was also one of the most complete ever discovered, with nearly 80% of its bone volume intact.

"A skeleton doesn’t usually end up complete, because there are lots of scavengers [in nature]," Anne said. "Things don’t get fossilized; they get recycled. Only when you’re very lucky, bones are preserved. That’s what happened with the T-rex."

From lost to found with 3D printing

The find, however, was not without its challenges, although Anne ironically calls them "small-scale." Enormous bones from the animal’s thigh, lower leg, and shoulder girdle were missing, creating an obstacle for the Naturalis team, which had plans to mount and display the skeleton for the public.

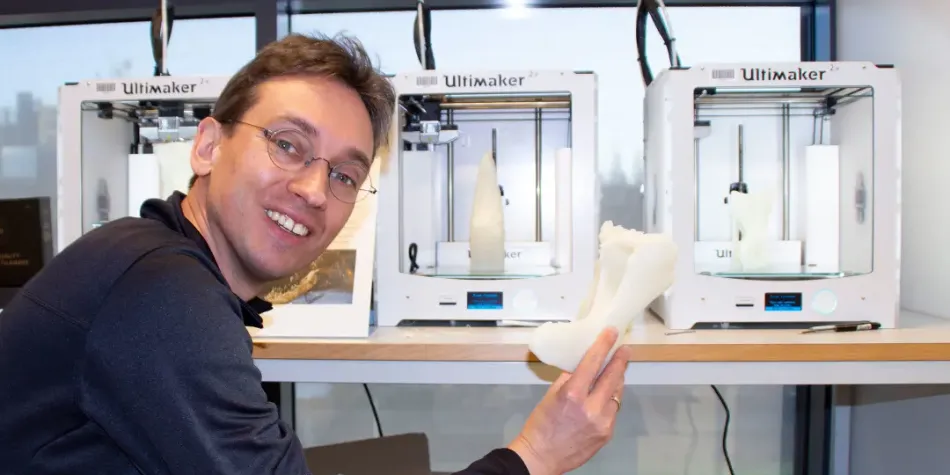

"You can’t make a cast, because you can’t mirror a cast. That’s one of the major advantages to 3D scanning and printing – you can mirror," Anne said. "The Ultimaker… was really accessible, both in terms of the hardware and the Cura software package that is seamlessly integrated. There’s not a steep learning curve. It was easy to set up. Everything just works. The enthusiasm of the Ultimaker team really helped as well — we had quite a bit of support."

The team first created mirrored copies of bones. These bones were then printed on Ultimaker 3D printers. The results were stunning – and culminated in a complete T. rex skeleton, named Trix, that was an "absolute delight to mount." The skeleton has since toured the world – stopping in Portugal, Scotland, Austria, France, and Spain – and is now back in the Dutch city of Leiden, its permanent home.

A return to a new home

While Trix was on tour, Naturalis underwent a complete renovation. Its interior is open, welcoming, its exhibitions increasingly interactive, making the museum a perfect place for learning, discovery, and exploration.

It has also become a hub for 3D printing. After its success with Trix, researchers at the museum began to use the technology for parts of other skeletons – namely those of five triceratops that can be seen around the museum. When found, the skeletons were severely disarticulated. With help from a museum in Indiana, in the United States, the team was able to scan certain bones from a similar specimen and size them to match. Other bones are mirrored. After they are 3D printed, they are painted and mounted, with special attention paid their appearance.

"We sort of try to get a slight difference between the real bone and the 3D printed material to make very clear what the difference is," Anne said. "It’s part of the story. We’re not pretending that an element that’s not real, is. If you look closely, you must be able to tell the difference. That’s important from an educational perspective."

Education, environment, and efficacy

That 3D printing can play a part in education is a bonus for both the technology and Naturalis. Dinosaurs, Anne said, are already great STEAM (science, technology, engineering art, and math) ambassadors. Throwing in a technology like 3D printing makes things even more fascinating, especially for young visitors. Today, they can enter the museum and see 3D printers – Ultimakers and larger-scale models – working to fully replicate Trix’s skeleton. When completed, it will be assembled and sent to a museum in Nagasaki, Japan for display.

“We had so many kids in the 3D printing lab — you just can’t keep them away from the Ultimaker," he said. "They want an Ultimaker for Christmas or their birthday. They set aside their pocket money because they want a 3D printer.

The choice to use 3D printers at Naturalis is, perhaps surprisingly, one partially made with the environment in mind. The process of creating casts and molds typically requires materials such as silicone, epoxy resins, and polyurethanes, which do not biodegrade – a fact at odds with the mission of most museums. Certain PLAs, on the other hand, are biodegradable, and many can be composted under the right, often deliberately set, conditions.

Additionally, all 3D printing at the museum is done with upcycled PLA filament, making the process even more environmentally friendly. In all, FFF technology has added a great deal of value to the way Naturalis operates, presents exhibits, and collaborates with paleontologists, museums, and educational institutes around the world. The quality of the final product is also effective. It enables researchers, scientists, and museum visitors to look at history in ways previously impossible.

"The level of surface detail, those sorts of things – they just shine; it’s much beyond what you’d expect," Anne said. "It’s hard to put a number on it, but the newness factor helped us in getting more funding. It was almost more of a return on enthusiasm than a return on investment."