The Quest for Automotive Lightweighting

When it comes to designing cars, saving weight is a top priority. But there is more to it than just swapping steel for aluminum, or tearing out the back seats.

This article was first published on

ntopology.comThe value of lightweighting in automotive reaches far deeper than zero-to-sixty times and top speeds. Safety, manufacturing costs, operating costs, and environmental sustainability can all directly benefit from more clever uses of materials in getting us from point A to B.

Lighter vehicles, all else equal, reach higher levels of performance: quicker acceleration, more agile cornering, higher top speeds, and shorter stopping distances.

Lighter vehicles can be safer vehicles: crashworthiness boils down to dissipating kinetic energy and transferring momentum, both of which scale with mass, and both of which require deformable and crushable hollow structures (more on this later) to do so.

Far from last, lighter vehicles are cheaper to operate, requiring less fuel or electricity per mile. Better fuel/power economy means fewer emissions as a result, amounting to environmental benefits as well.

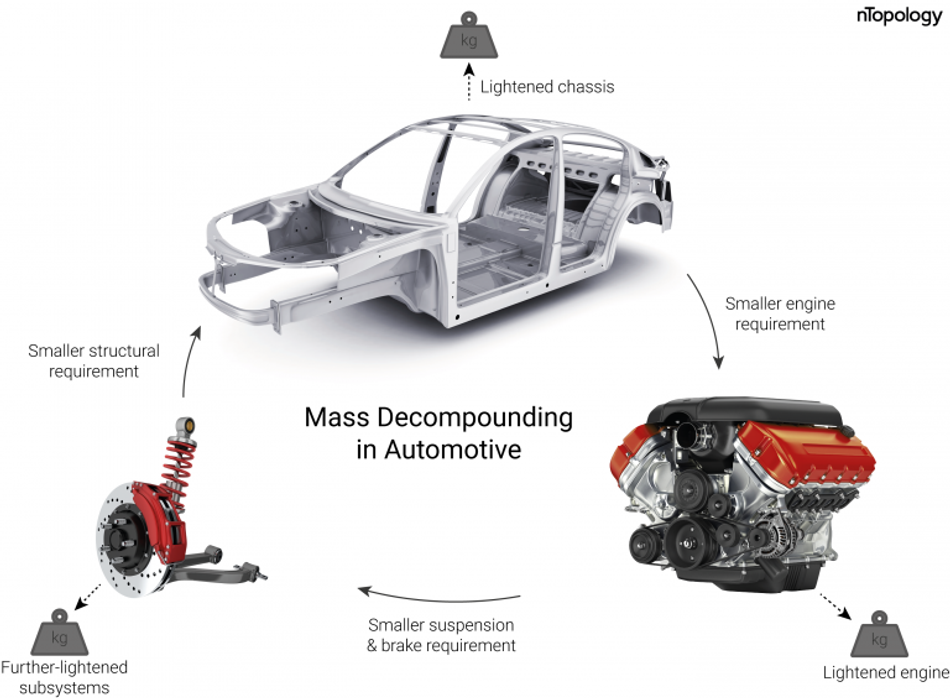

Compound Interest

Where things begin to get interesting is when these effects are coupled and the savings begin to compound and multiply. Weight eliminated from the chassis structure permits the use of a smaller and lighter motor, and lighter brakes and suspension. Now the whole vehicle weighs substantially less, and the chassis can be revisited and lightened further. This all adds up to a potentially higher performance, safer, and more efficient vehicle.

This can be even more dramatic with electric vehicles, where the dense batteries make up a considerable fraction of the vehicle’s mass. With electric vehicles still (as of writing) playing catchup with the range of their combustion-powered competitors, every extra mile becomes a key value proposition at the dealership.

These are referred to as “secondary mass savings”, or “mass decompounding”. If you’re interested, you can read more about these in this paper from MIT and General Motors [1]. With a blank-sheet design opportunity, they estimate that (on average) every pound of savings on structural, load-bearing parts provides an opportunity to save nearly a pound on subsystems (steering, brakes, suspension, etc.). That’s essentially a two-for-one deal! This figure decreases as the design cycle progresses and subsystems are locked in, so lightweighting should be considered in design as early as possible to maximize these compounding effects.

Beyond the Vehicle

Lightweighting applies to more than just the vehicle: the millions of pounds of jigs and fixtures on an assembly line are all candidates for lightweighting. Lighter tooling, besides using less material, is easier on both human and robotic operators alike, potentially unlocking higher production rates. Lastly, transporting lighter vehicles to dealerships and customers results in even more indirect cost savings of lightweighting.

Does lightweighting come for free? Certainly not. But with the aforementioned value propositions, it is easy to see why there is so much focus on it in the automotive industry today.

Making Progress

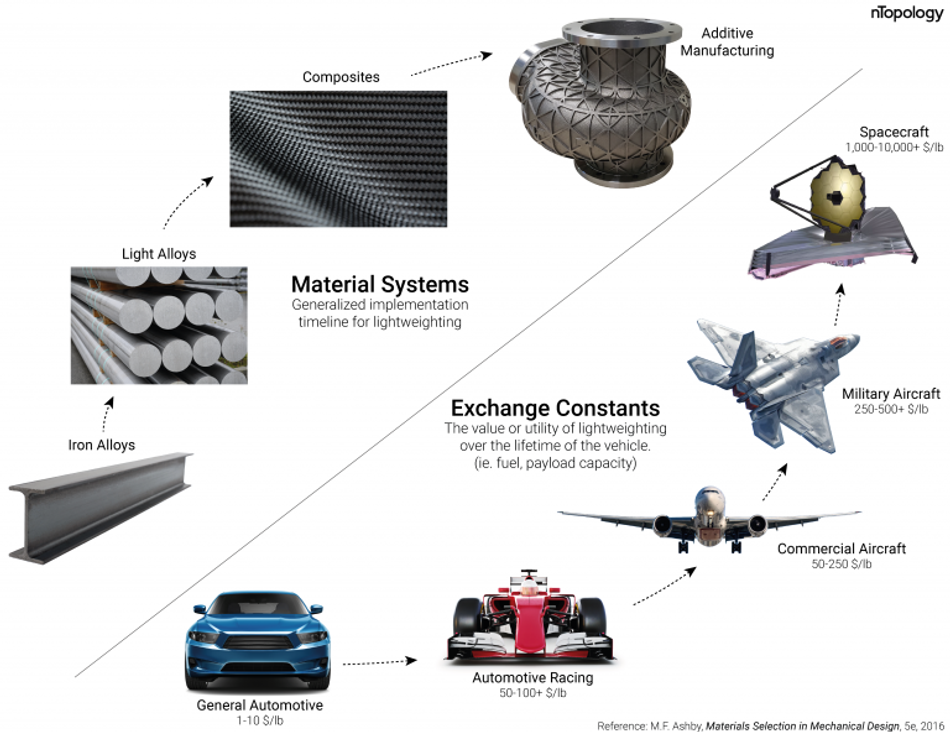

New technologies almost always cost more than what they replace, at least during their initial implementation. Aluminum was once seen as an aerospace-only material due to cost, with cast iron and steel dominating the automotive bill-of-materials for many years. This is almost surprising to realize in retrospect, with aluminum now so widespread in our cars today. We are right in the midst of the same phenomenon with composites. Not long ago, carbon-fiber composites were relegated to aerospace and Formula One, eventually trickling down to the supercar market. Now they are rapidly expanding into the mainstream market, with some manufacturers already building large body panels entirely from composites for family sedans and small hatchbacks.

Koenigsegg appeared to have launched the metal additive trend for production end-use parts in 2014, with a 3D-printed stainless steel variable turbocharger, and a 3D-printed titanium exhaust component which saves a kilogram over its machined aluminum predecessor [3]. Of course, this is a 1300+hp multi-million-dollar vehicle, but it marks the start of the metal additive age in automotive. Since then, several larger manufacturers have begun to adopt additive in serial production at much larger production volumes. This trend will only continue as the manufacturing technologies mature and become less expensive, just as they did with light alloys and carbon fiber.

Unlike light alloys and composites, however, the expansion of additive technologies may also eliminate a significant amount of tooling (a substantial investment in both time and cost for manufacturers) — both through part consolidation and technological progress towards nearer-net-shape finishes in additive processes.

Challenges Remain

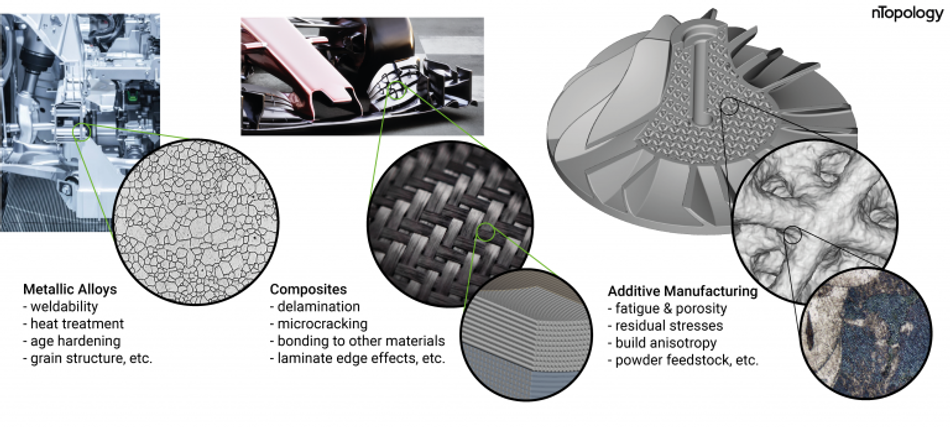

Unfortunately, lightweighting is not as simple as substituting in these new, lighter, and stronger materials. Even if it were, the opportunity of that new material or process would likely be underutilized. Recall the ‘black aluminum’ phenomenon with composites: simply rebuilding a sheet metal design with a composite was not the best use of this new material, nor were conventional simulation and validation approaches suitable [4]. Things like anisotropy, ply stack terminations, size/edge effects, etc. were all new effects to consider in the design process.

Engineers had to start at a micromechanical level, first understanding things like fiber-matrix failure mechanisms and establishing certification methods, and then working their way up to design guidelines and repeatable workflows and processes. Years later, however, composites are everywhere, and it is hard to envision going back without them. It is much more a gentle transition than an overnight revolution.

The same is true for additive manufacturing and advanced generative/organic topologies. It is perhaps even more true for lattice structures and architected materials, though the potential return on these is also much greater. With additive’s much less restricted design space (any reader still remaining at this point will likely agree that ‘unrestricted’ is not entirely accurate for AM), generating and iterating on design candidates becomes burdensome with conventional modeling tools.

If creating the models is difficult and slow, so will be the simulation and validation—which is even more critical now that we have less wiggle room and factor-of-safety to work with as we approach an optimum solution. A somewhat synergistic effect is that, due to the fact that these advanced manufacturing technologies and materials generally cost more per pound, there is even more motivation to use them efficiently.

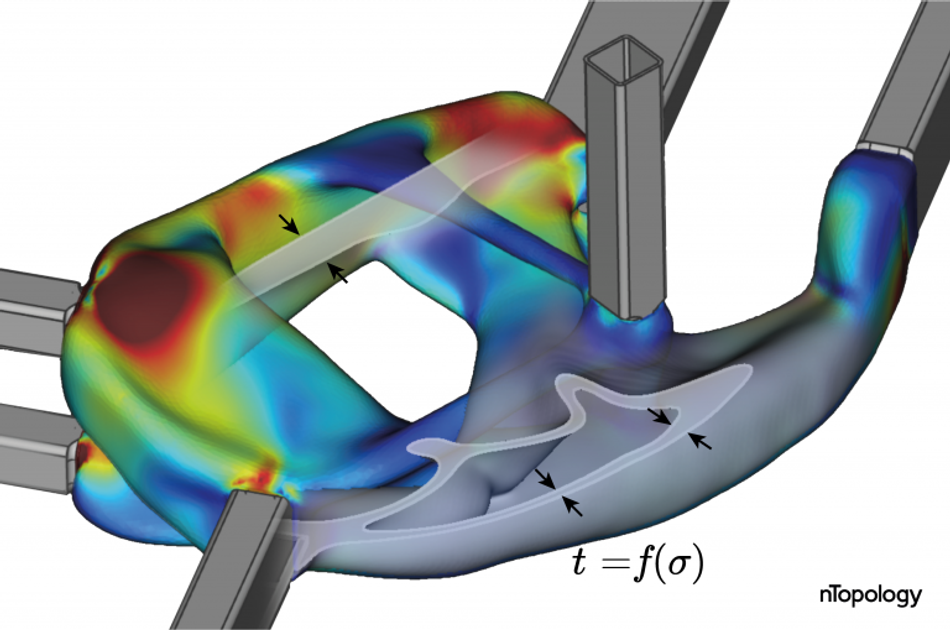

With topology-optimized (or “generative”, if you prefer) designs, a key obstacle to real implementation is that the results are often solid lumps, formed by simple compliance minimization algorithms. The trouble here is that solid blobs do not collapse and crush very smoothly, and crashworthiness engineers often require hollow tubes instead. As any CAD engineer would know, however, shelling a complex organic part can be an unexpectedly difficult task, even if it is just of constant wall thickness (unlikely to be an optimal distribution of material). Conventionally, engineers have struggled to manufacture what they design; but with additive, it is often reversed: it can be a struggle to design what you’re able to manufacture.

Opportunities and Outlook

Materials and process improvements are well underway and have been showing remarkable progress. Once prohibitively expensive, technologies like carbon fiber composites are becoming cheaper and cheaper, with compression molding of chopped fibers already making the business case in mainstream vehicles. Once-niche technologies like metal powder bed fusion, which skeptics once said would never exceed a 200 mm build plate edge length, are now reaching the 1000 mm meter mark with multiple laser sources.

However, advanced materials are only as effective as the shapes in which they are formed; topology is half the battle. One aspect that has been lagging behind, and is now becoming an increasingly glaring bottleneck, is in the fragmented and expensive alphabet soup of upstream design tools (CAD, CAM, CAE, etc.).

It is surprising how many hours (and therefore dollars) each handshake between these acronyms can actually represent. We sometimes hear of days being spent to reconstruct the native geometry of a shape-optimized density field, and weeks wrestling sketch relations and offsets if one were to shell it for crashworthiness requirements. The latter of course then requires remeshing and revalidating to locally adapt the wall thickness, and will hopefully be the final iteration of this whole process (which it rarely is). The design effort required to trim out those final few pounds increases exponentially.

There is a glaring need in the industry for design tools that are built on solid and modern foundations; foundations designed for these new materials and technologies. However, just as some classical materials still have their place in production (cast iron brake disks and engine blocks), so too will existing tools and procedures, like clay modeling or drafting in CAD. Mixed-material design is becoming increasingly common, with steels, plastics, aluminum alloys, magnesium alloys, and carbon composites all coexisting in the same vehicle platform. We’re learning to bond and hybridize very dissimilar materials to reach new levels of automotive performance, and there is no one-size-fits-all wonder material.

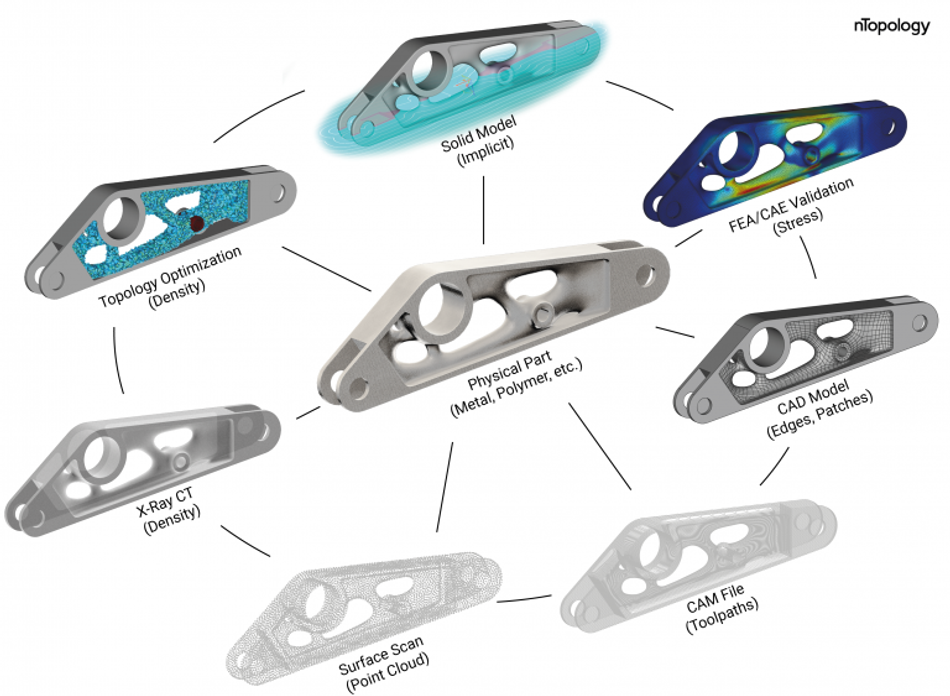

In the quest for lightweighting, the same will hold true of design tools. Instead of mixed-materials, we have mixed data sources: surfaces from CAD, meshes from FEA, density fields or stress results from CAE, and real-world measurements like scan data or digitally-imaged strains. Just like physical materials, these too can be synthesized and fused together digitally to reach new levels of performance.

We need new tools to do this mixed-material, multi-objective design and optimization process — with consideration of all of the mixed data sources being used where they’re best suited. This is where computational modeling fits in, enabling this data-fusion approach to engineering design where the many factors and measurements relevant to the engineering process can be synthesized into one high-performance design representation. With this new multi-factor approach to design, we can begin to fully exploit the many simultaneous lightweighting opportunities available in automotive.

Are you looking for more content on lightweighting in automotive? Check out what Fabian Grupp has to say about the European Green Deal and its impact on automakers in Germany. Read now.

References

[1] E. Alonso, T.M. Lee, C. Bjelkengren, R. Roth, R.E. Kirchain, “Evaluating the Potential for Secondary Mass Savings in Vehicle Lightweighting”, Environmental Science and Technology, 2012.

[2] M.F. Ashby, Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, 5e, 2016

[3] 3D Printing: Titanium, Carbon Fiber, & The One:1 – /INSIDE KOENIGSEGG [Video Interview, The Drive, 2014]

[4] S. Black, “Getting To Know “Black Aluminum”: An introduction to CFRP”, Modern Machine Shop, 2008.

[5] Image from: Grain Size Analysis in Metals and Alloys, Olympus Industrial Resources.

R. Heuss, N. Muller, W. van Sintern, A. Starke, A. Tschiesner, “Lightweight, heavy impact”, McKinsey & Company, “Advanced Industries” Series, 2012.

A. Weber, “Lightweighting Is Top Priority for Automotive Industry”, Assembly Magazine, 2018. Link

This article was first published on the nTopology blog.