Electrochemistry helps clean up electronic waste recycling, precious metal mining

A new method safely extracts valuable metals locked up in discarded electronics and low-grade ore using dramatically less energy and fewer chemical materials than current methods, report University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers in the journal Nature Chemical Engineering.

A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign shows how electrochemistry can be used to extract precious metals from discarded electronics in an efficient and environmentally friendly manner. Photo by Fred Zwicky

This article was first published on

news.illinois.eduGold and platinum group metals such as palladium, platinum and iridium are in high demand for use in electronics. However, sourcing these metals from mining and current electronics recycling techniques is not sustainable and comes with a high carbon footprint. Gold used in electronics accounts for 8% of the metal’s overall demand, and 90% of the gold used in electronics ends up in U.S. landfills yearly, the study reports.

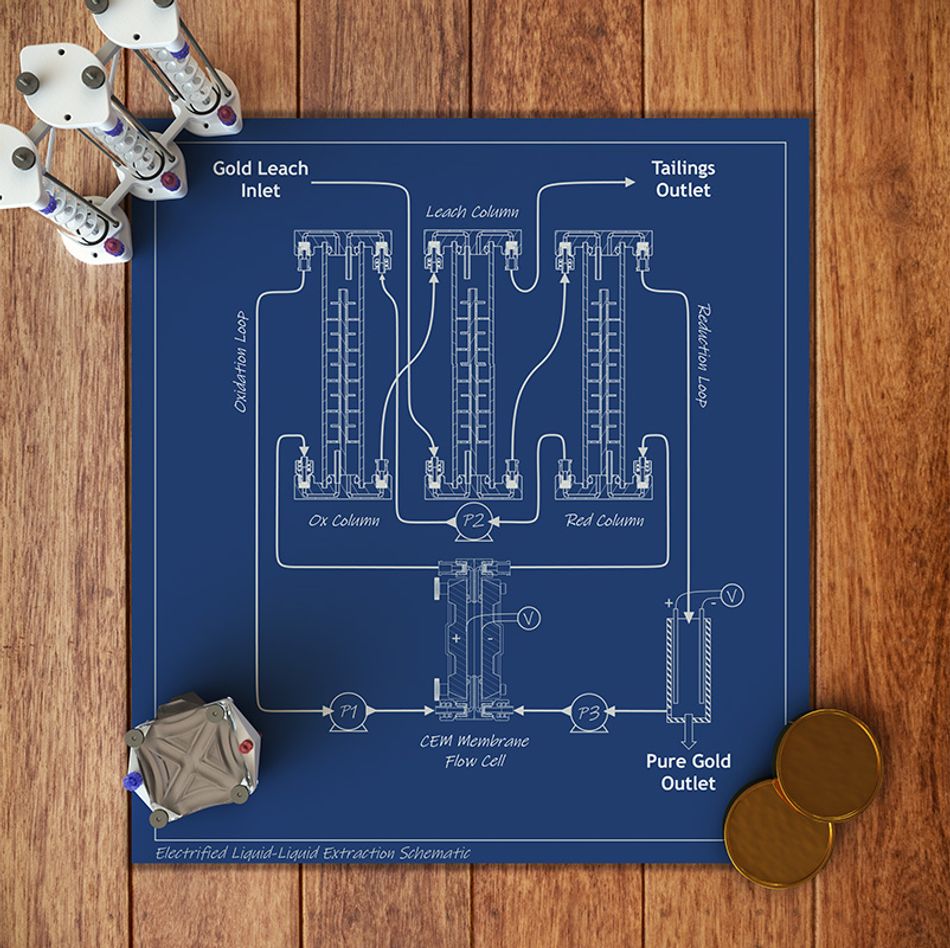

The study, led by chemical and biomolecular engineering professor Xiao Su, describes the first precious metal extraction and separation process fully powered by the inherent energy of electrochemical liquid-liquid extraction, or e-LLE. The method uses a reduction-oxidation reaction to selectively extract gold and platinum group metal ions from a liquid containing dissolved electronic waste.

In the lab, the team dissolved catalytic converters, electronic waste such as old circuit boards, and simulated mining ores containing gold and platinum group metals using an organic solvent. The system then streams the dissolved electronics or ores over specialized electrodes in three consecutive extraction columns: one for oxidation, one for leaching and one for reduction.

“The metals are then converted to solids using electroplating, and the leftover liquid can be treated to capture the remaining metals and recycle the organic solvent,” Su said. “The stream containing the organic extractant is then pumped back to the first extraction column, closing the loop, which greatly minimizes waste.”

An economic analysis of the new approach showed that the new method runs at a cost of two orders of magnitude lower than current industrial processes. “The social value of this work is really its ability to produce green gold quickly in a single step, greatly improving transparency and trust in conflict free recycled precious metals,” said postdoctoral researcher Stephen Cotty, the first author of the study.

Su said one of the many advantages of this new method is that it can run continuously in a green fashion and is highly selective in terms of how it extracts precious metals. “We can pull gold and platinum group metals out of the stream, but we can also separate them from other metals like silver, nickel, copper and other less valuable metals to increase purity greatly – something other methods struggle with.”

The team said that they are working to perfect this method by improving the engineering design and the solvent selection.

Research scientist Johannes Elbert and graduate student Aderiyike Faniyan contributed to this study. Su also is affiliated with the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology and a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Illinois.

The U.S. Department of Energy supported this study. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has filed a provisional patent on the technology presented in this work. The authors declare no competing financial interest.