Robot-assisted feeding the focus of 1.5M USD NSF grant

Tapomayukh Bhattacharjee has been working on assistive robotics for approximately a decade, and in speaking to the people who would benefit from new technologies, he’s come to a few realizations.

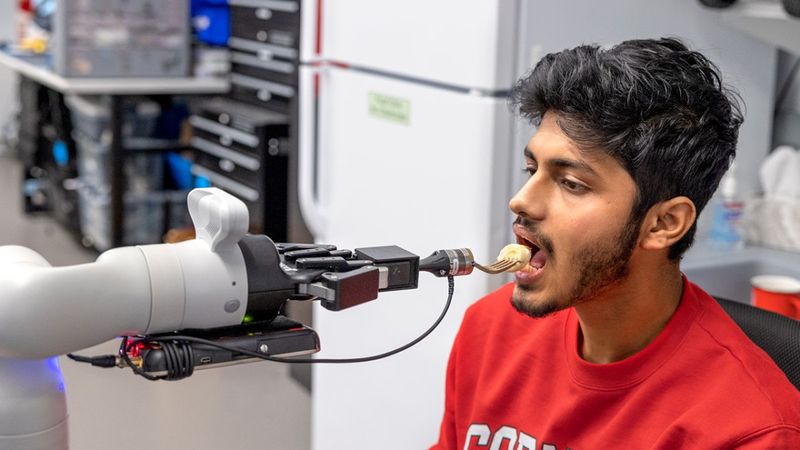

Doctoral student Rajat Kumar Jenamani, a member of Tapomayukh Bhattacharjee’s EmPRISE Lab, prepares to take a piece of a banana from an assistive robot prototype. Ryan Young/Cornell University

Tapomayukh Bhattacharjee has been working on assistive robotics for approximately a decade, and in speaking to the people who would benefit from new technologies, he’s come to a few realizations.

“I started chatting a lot with the stakeholders – people with mobility limitations, the caregivers who are helping them, and occupational therapists – and I felt like robotics can truly make a difference in their lives, when it’s ready to be deployed,” said Bhattacharjee, hired in July 2021 as an assistant professor of computer science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

Tapomayukh Bhattacharjee received a National Robotics Initiative collaborative grant for a project that aims to address the way people with mobility issues are given a chance for improved control and independence over their environments, especially how they are fed.

Among the basic activities of daily living that robotics could impact, Bhattacharjee is currently focused on eating. And a four-year, $1.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation’s National Robotics Initiative will help him and his EmPRISE Lab develop assistive robotics for people with physical disabilities and their caregivers.

“Feeding is one of the most basic activities,” he said. “Imagine yourself asking someone else to feed you every morsel of food in your day-to-day life. It just completely takes away the sense of independence. And so, if we could solve this feeding challenge, if a person could perceive this robot as an extension of their own body, then they will feel much more independent. That’s why I am so passionate about solving this.”

Bhattacharjee – who received his Ph.D. in 2017 from the Georgia Institute of Technology, and developed a prototype robot during his postdoctoral work at the University of Washington prior to joining the Cornell Bowers CIS faculty – fully understands the nature of the challenge in front of him.

“Despite great strides taken toward sustainable solutions in controlled environments,” he wrote in his grant proposal, “robots are far from ready for adoption in real-home environments as long-term caregiving solutions.”

To address the eating challenge, Bhattacharjee will focus on three key elements:

- Bite acquisition: His team will derive algorithms that learn by obtaining human feedback – which they refer to as human-in-the-loop manipulation – to perform difficult tasks related to eating, particularly with different forms of food;

- Bite transfer: The goal is to develop safe control and learning algorithms for bite transfer – that is, the robot actually placing the food safely in a person’s mouth, particularly if the person has profound physical limitations and cannot move to take the food; and

- Feeding with user preferences: The team will develop active learning and shared autonomy algorithms that capture, over time, human preferences of bite transfer trajectories.

“The main lessons we learned in our experiments [at Washington] was that every user is different,” he said. “Everybody has their personal preferences. And if we really want a long-term caregiving solution, the solution needs to be personalized to the user. And just like a patient and a caregiver need time to get used to each other, it’s the same with a patient and a robot.”

The main target population Bhattacharjee is focusing on with his assistive technology is people with spinal cord injuries – those who are limited physically but not necessarily cognitively, so they would be able to help train the robot.

One key element of the work will be leveraging the idea of human feedback – specifically by embracing the inevitable physical contact between the robot and human, such as when placing the utensil inside the mouth.

“If you think about robots in airports, self-driving cars, robots in grocery stores, it’s all about avoiding obstacles,” Bhattacharjee said. “But realistically, if I’m grabbing for something, my arm might touch something else, right? The whole point is, can we leverage this contact, while being safe and efficient at the same time?”

The grant period starts Jan. 1, 2022, and runs through 2025.