We Just Created The Deepest Deepfake Yet. Here's Why.

Raising Awareness About The Dangers of Synthetic Media

If you think this is an image of Joe Rogan, think again. It’s actually a frame from a hyper-realistic deepfake we created, overlaid with an AI facsimile of his voice. Learn more after the jump.

Introduction

In a small meeting room on a Tuesday morning, I showed a short video we created to the people in the room. After it finished I glanced over to find the first and only journalist to win four Pulitzer Prizes with his head in his hands, contemplating the end of truth and reality as we know it. How did we get to this place?

A new version of the deepfake video we initially shared with The NYT is now available on YouTube.

Earlier this summer, our company Dessa became known around the world for making the most realistic AI voice to date, which replicated one of the most famous voices in podcasting, Joe Rogan. The AI voice, which was built using a text-to-speech synthesis system we developed called RealTalk, could say any words we wanted it to say, even if Rogan had never said them before.

We didn’t just do this for kicks. One of our main objectives with releasing RealTalk was to get the public to take notice of just how realistic deepfakes were becoming, and to understand the tremendous implications at hand for society as a result.

It worked.

Since we released RealTalk in May, we have been shocked by the huge wave of public reception to it. More than 2 million people have viewed our video featuring clips of the faux Rogan voice on YouTube. Awareness about the work also quickly spread around the world, with journalists from over 20 different countries covering it (you can find a selection of the news coverage here).

One of the journalists who became interested in the work was David Barstow, the journalist we mentioned earlier, who emailed us shortly after we shared RealTalk publicly. At first, I had to do a double take to see whether or not the email was a prank. Here was someone who had taken on some of the world’s biggest stories (most recently, revealing Trump’s tax evasion schemes), getting in touch with us, wanting to work with us on a story about deepfakes.

Not nervous or heart-attacky at all, I agreed to have a call with him the same day. David said he had first become interested in learning more about deepfakes after seeing his son showed him a video of a now legendary deepfake that Jordan Peele had created of Obama, and was thinking of their implications especially as the 2020 American election drew nearer.

During the call, David asked me if we had thought about pairing synthetic audio with synthetic video to create a fully fledged deepfake (one that would be nearly impossible to discern as fake), and likened such a feat to an Edison moment. If the team were to attempt such a project, he wondered, would we also be interested in being filmed during the process, and ultimately becoming the subject of a documentary on The Weekly?

We had to pinch ourselves after that initial phone call. But we were confident that if anyone could distill why it was important for the world to know about deepfakes, it was David Barstow. And the truth was, it was like he had read our minds. Shortly after releasing RealTalk, and before we had that call, we had already started to think about merging audio and video as a next phase of the project, certain it would help us in our mission to spread even more awareness about the power and danger of deepfakes.

After that call with David, we quickly decided that opening our doors to The New York Times in the way we did was a no-brainer. Having the work showcased in a documentary by The Times would mean that millions more people would become aware of deepfakes and their implications. And we would have the credibility of The New York Times behind us. It really seemed like the ultimate soapbox for our message.

At the same time, along the way we were starkly aware of the risk it simultaneously posed to our reputation. What if they took our work, but chose not to share the intentions we had behind it? There was a huge risk that we would come across as evil geniuses or, less worse, idealistic tech bros. But ultimately, we determined that this was a risk worth taking.

Six months later, we’re excited to share this work with the world.

It may not seem like it, but the timeline we set aside to create this work was a very short one (especially since we were juggling many other projects simultaneously throughout this period). To maximize our control of the message, however, we knew we would have to act fast, since we were confident many others with machine learning expertise would be working on similar projects at the same time we were.

The unfortunate reality is that at sometime in the near future, deepfake audio and video will be weaponized. Before that happens, it’s crucial that machine learning practitioners like us who can spread the word do so proactively, helping as many people as possible become aware of deepfakes, and the potential ways they can be misused to distort the truth or harm the integrity of others. Ultimately that is why we decided we had to be the first to reach the finish line.

At this point, it’s also worth noting that we will not be sharing the model, code or data used to create the deepfake publicly. You might be thinking that this sounds extreme, unfair to ML researchers, or just a rehashing of Open AI’s decision to do a staged release of the GPT-2 language processing model (the AI that was “too dangerous to release”) first announced earlier this year.

It isn’t, because the reality is that tools for generating synthetic audio and video (and especially for generating them in tandem) are a lot more dangerous. If we were to open source the tools we used to make RealTalk, they could actually be used to scam people as individuals, or disrupt democracy on a mass scale, and it wouldn’t be that hard. In contrast, for an individual to use a model like GPT-2 to spread disinformation, they would need to somehow make tons of fake news websites, and also get traffic to them.

That said, there are select pieces of information we can share about the technical process of creating the work we feel comfortable sharing. Here is a brief overview of the building blocks we used to create our hyper-realistic deepfake video of Joe Rogan announcing the end of his podcast.

Technical Overview

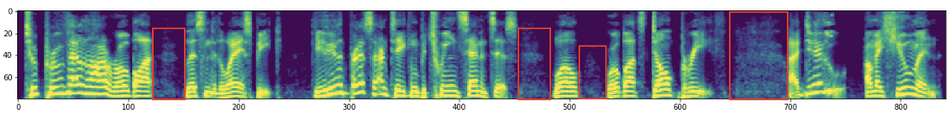

Audio: To synthesize the audio used in our final version of the video, we used the same RealTalk model we developed to recreate Joe Rogan’s voice with AI back in May. RealTalk uses an attention-based sequence-to-sequence architecture for a text-to-spectrogram model, also employing a modified version of WaveNet that functions as a neural vocoder.

The final dataset our machine learning engineers used to replicate Rogan’s voice consists of eight hours of clean audio and transcript data, optimized for the task of text-to-speech synthesis. The eight-hour dataset contains approximately 4000 clips, each consisting of Joe Rogan saying a single sentence. The clips range from 7–14 seconds long respectively. You can find a more in-depth blog post about the technical underpinnings of RealTalk we released earlier this summer here.

Video

For the video portion of the work, we used a FaceSwap deepfake technique that many in the machine learning community are already familiar with. The main reason we chose the FaceSwap instead of other techniques is that it looked realistic and was pretty reliable, without requiring many hours of training data to employ properly. This was an important factor for us due to our expedited timelines. To use the FaceSwap technique, we would only need one high-quality and authentic video of Joe Rogan to use as source data, and an actor who resembled him for the video we would use to swap Joe Rogan’s face onto. We ultimately picked Paul, shown below, because his physique closely resembled Joe Rogan’s.

Combining Audio & Video: Combining the synthetic audio and synthetic video together is the most difficult part of the process, because there are multiple disconnected steps in the process that make it hard to perfect. First off, the fake audio is generated separately from the video. The fake audio replicates the tone, breathing and pace at which the target speaks (in this case, Joe Rogan). For the video to look convincing, the actor posing as Rogan needed to match the same expressions and speed as the synthesized audio.

This presented us with a huge challenge, as the actor had to focus not only on copying the original audio exactly to ensure a lip sync, but also copying the expressions of the audio, as well as moving and behaving in a natural way. The first time either of the actors did manage to match the lip-sync, they basically just stared into one spot unblinkingly while copying the lip movements. Unless we were replicating a robot from an 80s sci-fi movie, this likely wouldn’t be very convincing.

Recommended reading: The pandemic of deepfakes : A rising threat bigger than identity theft

In short, building a deepfake convincing enough to fool everyone is thankfully something that for now is still really hard to do. But this won’t be the case forever.

Conclusion

Why Building Awareness Is Crucial

Dessa may have achieved a deepfake merging audio and video at this level of high fidelity first, but we will not be the only ones to do it. Many others are working on the same technology, and future versions of this will be much faster and easier to use than ours. As mentioned above, the reality is that deepfakes can (and are already are) being used for malicious purposes.

We need to make sure as many people are aware of how advanced this technology is, and we need to do it fast. Malicious actors will move way faster than the rest of us, because they don’t care about getting things perfect and don’t have bureaucracy slowing them down. They will simply do whatever it takes to demean innocent individuals, steal money, or disrupt democracy.

Next steps: Contributing to the field of deepfake forensics

Our machine learning engineers’ development of hyperrealistic deepfakes has also led us to examine what we can do to help make detecting them easier and more reliable in the wild. Earlier today, we shared a new technical blog post from our engineers that shows how a recent dataset released by Google for deepfake detection falls short at reliably identifying fake videos found in the wild on YouTube. After demonstrating where the dataset falls short, our engineers have also provided a solution for making it more robust and functional on real-world data. This work has also been open-sourced for anyone wanting to replicate and expand on our results over on GitHub. The work we did on deepfake detection was featured today in The New York Times by Cade Metz, the newspaper’s AI Reporter. Find the article here.

Earlier this fall, we also released an article and open source tools for building systems for detecting deepfake audio, which you can find respectively on our Medium and GitHub.