With a single paper sheet, engineers make dancing structures that direct light and sound

Combining insights from two ancient art forms, Princeton engineers used a single sheet of material to create 3D structures with adjustable flexibility that could guide sound and light to perform complex tasks.

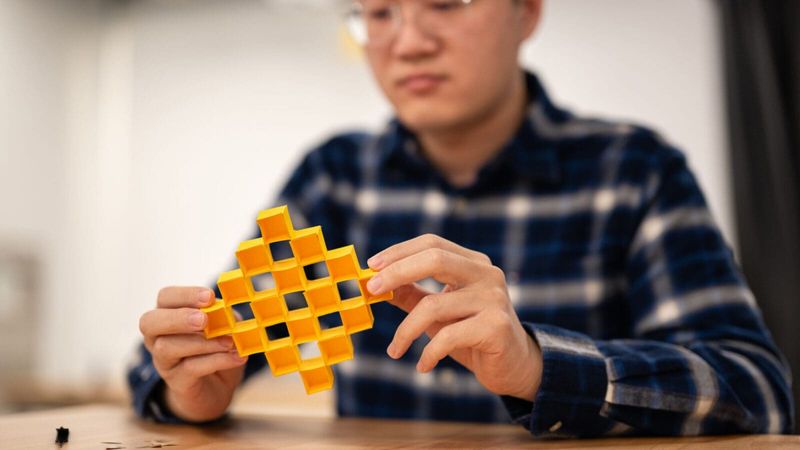

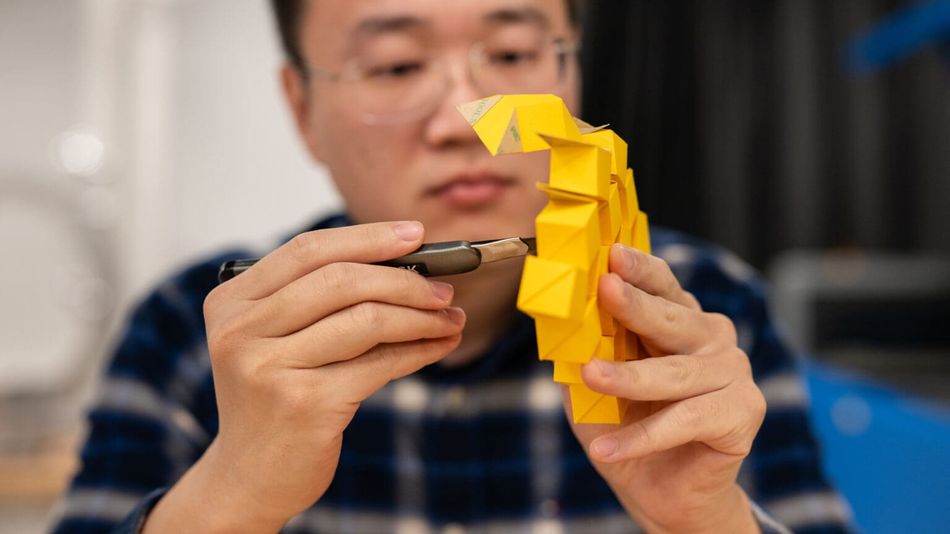

Xiangxin Dang, a postdoctoral researcher, displays an adjustable structure made from a cardboard sheet. Photos by Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy

This article was first published on

engineering.princeton.eduIn an article published Nov. 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a research team led by professor Glaucio Paulino reported that they used strategic cutting and folding to turn a single sheet of paper into a metamaterial — a material that demonstrates unique properties based on form and geometry. An egg carton, which is stronger than a sheet of cardboard, is a simple example.

Paulino said the researchers used aspects of paper cutting, or kirigami, to transform a sheet of paper into a complex surface with a large number of holes, which mathematicians call a high-genus surface. The researchers then applied folding techniques based in origami to turn the paper into a three-dimensional structure. However, most of the work involved exploring the underlying mathematics behind the combined patterns of cuts and folds and working out algorithms that engineers can use to create metamaterials with desired properties.

“Combing the two disciplines is not as simple as cutting a piece of paper and folding it,” said Xiangxin Dang, a postdoctoral researcher in Paulino’s lab and the article’s lead author. “It involves a careful balance between the two ideas.”

Dang said the balance between the cuts and folds allows designers to create a network effect among shapes that are connected with hinges. This allows designers to create adjustable, three-dimensional structures that can be tailored to respond to outside forces like pressure. For example, a structure could be rigid in one direction and flexible in another. With a simple twist, the structure can alter flexibility as its geometry changes.

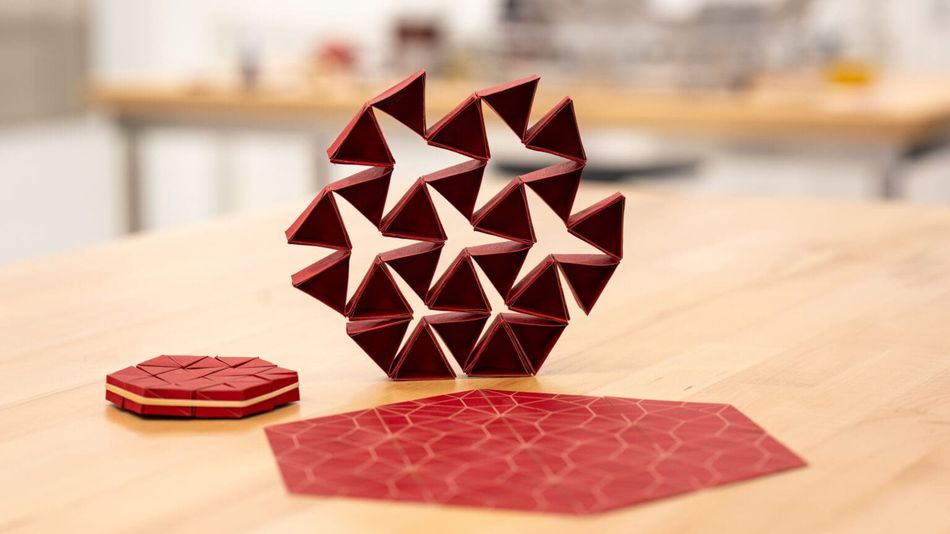

Paulino said designers can create shapes that use the structure to introduce polarity — the ability to guide flow in one direction. Electric circuits are an example of polarity. But unlike electric circuits, the new metamaterial uses geometry rather than electromagnetic fields to generate polarity. With additional work, he said engineers could use the technique to create geometric circuits to guide sound.

“It’s just one piece, which makes it easier to work with and with less chance for mistakes in manufacturing,” said Paulino, the Margareta Engman Augustine Professor of Engineering. “By combining cuts and folds into high-genus surfaces, we can introduce polarity into an adjustable, folded structure. Eventually, this could be used for optics and semiconductors.”

Paulino said the patterns of cuts in the sheet before folding show a surprising lack of symmetry. To achieve the properly folded structure, “you have to break a lot of symmetry,” he said.

The work grew out of an earlier experiment with a folding structure that did not work. But Paulino said the results pointed to an approach that led to the system that allowed the researchers to introduce polarity into the 3D structure. The ability to make informed mistakes, Paulino said, can be rewarding. “When you have an idea, most of the time it does not work,” Paulino said. “But sometimes, when you make a mistake, it generates something interesting.”

The article, “Folding a single high-genus surface into a repertoire of metamaterial functionalities,” was published Nov. 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Besides Paulino and Dang, the authors included Stefano Gonella, a professor of engineering at the University of Minnesota. A commentary by Zeb Rocklin also appeared in PNAS. Support for the research was provided in part by the National Science Foundation.