Welding Metal Foam

Composite metal foam could make aircraft wings or armor simultaneously stronger and lighter. An advanced material, the properties of composite metal foam (CMF) indeed make it attractive for a wide range of applications.

An F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter jet sits onboard an aircraft carrier deck sailing the ocean.

This article was first published on

news.ncsu.eduComposite metal foam could make aircraft wings or armor simultaneously stronger and lighter. An advanced material, the properties of composite metal foam (CMF) indeed make it attractive for a wide range of applications.

There’s a problem, though. To bring many of those applications to life, manufacturers must be able to weld CMF components together — without impairing the properties that make it so attractive.

Researchers at NC State University might have found a solution. It’s called induction welding.

“Most forms of traditional welding don’t work well with metal foams,” says Afsaneh Rabiei, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at NC State and corresponding author of a paper on the new research.

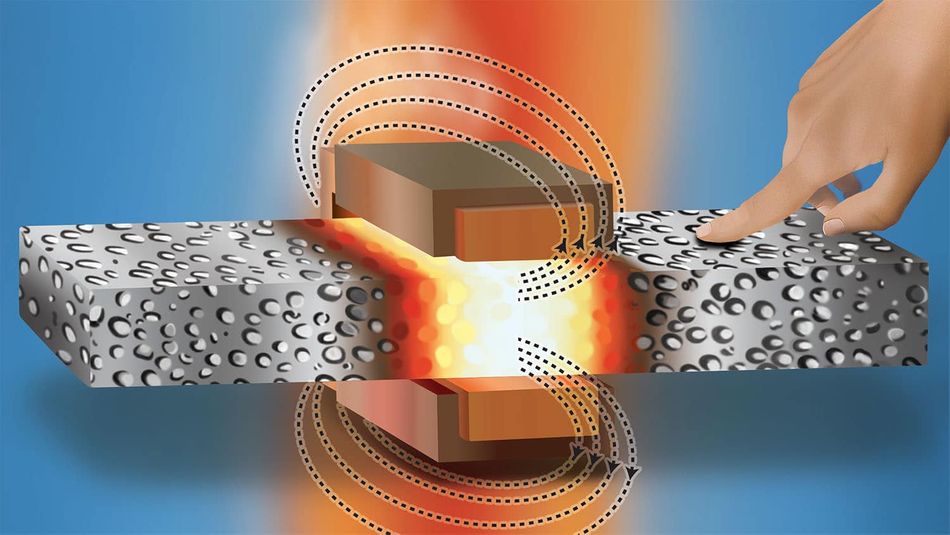

Induction welding, as the name implies, uses an induction coil to create an electromagnetic field that heats the metal. Rabiei and the research team published findings that indicate induction welding works very well on CMF components.

Commonly made out of stainless steel or titanium, CMFs are foams that consist of hollow, metallic spheres. These pockets of air in CMFs make the material light, strong and effective at insulating against high temperatures.

“Traditional fusion welding uses a filler to connect two pieces of metal,” Rabiei says. “This is problematic because the metal being melted to fuse two pieces of CMF is solid, so it lacks the desirable properties of the CMF on either side of it. In addition, any type of welding that uses direct heat to melt the metal results in some of the porosity in the CMF being filled in, which impairs its properties.”

Rabiei says CMF is only 30-35% metal. So the electromagnetic field created by induction welding can “penetrate deeply into the material — allowing for a good weld.”

Meanwhile, the air pockets that make up the remaining 65-70% “serve to insulate the material against the heat,” which allows a welder to heat a joint without the heat spreading too far.

“That helps to preserve the CMF’s properties,” Rabiei says.

Together with NC State Ph.D. students John Cance and Zubin Chacko, Rabiei published “A Study on Welding of Porous Metals and Metallic Foams” in the journal Advanced Engineering Materials late last year.

This article is based on a news release from NC State University.