FFF vs FDM: Is There Any Difference?

Fused filament fabrication (FFF) and fused deposition modeling (FDM) both refer to a type of extrusion 3D printing. So why the two terms?

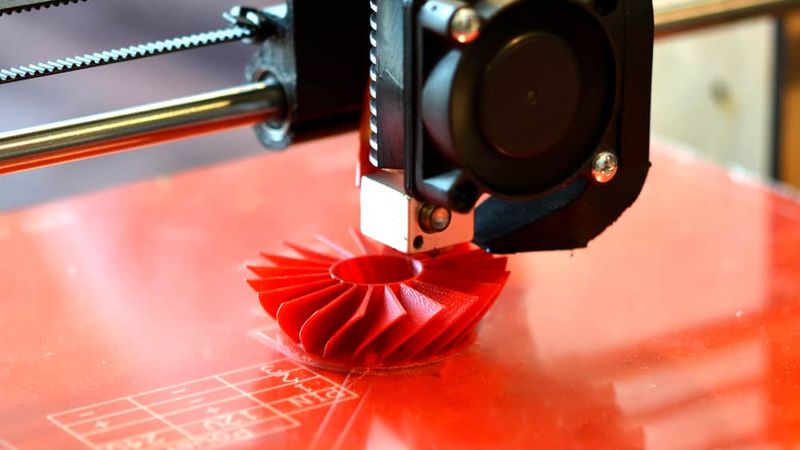

FFF vs FDM? The two terms refer to the same extrusion printing technology

The world of 3D printing is full of technical-sounding terms for technologies, often accompanied by a three-letter acronym. In addition to FDM and FFF — to be explained in this article — you’ve got SLA, SLM, SLS, MJF, PBF, and more.

The confusing thing about these acronyms is that some of them are generic terms (used to describe a technology regardless of who developed it) and some of them are proprietary or trademarked terms. For example, while “SLM” (selective laser melting) is often used to describe a broad category of metal additive manufacturing processes, it is actually a proprietary term owned by German company SLM Solutions. “PBF” (powder bed fusion), a generic term, can be used to describe the same process.

This use of both generic and proprietary terms leads to plenty of confusion, especially when two terms are used to describe what appears to be the same thing. This is the case with FFF vs FDM: “FFF” is a generic term for a type of extrusion 3D printing technology, while “FDM” is a proprietary, trademarked term used exclusively by the company that invented that technology.

This article discusses FFF vs FDM from a legal and practical perspective and explains when to use one or the other.

What Are FFF and FDM?

FFF (fused filament fabrication) and FDM (fused deposition modeling) are two terms for the same type of 3D printing (additive manufacturing) technology that uses thermoplastic filament as feedstock.

FFF/FDM 3D printers are fitted with a spool of filament, which is fed continuously to a heated extruder head (the “hotend”) where it is melted and extruded through a nozzle onto a flat “print bed” underneath. Controlled by computer instructions, the printhead moves along the X/Y plane, laying down the material into a precise 2D shape. Once an entire 2D layer has been printed, the printhead or bed makes an incremental movement, then the printhead lays down the next layer on top of the first. By the end of the process, a solid 3D shape has been created.

The FFF/FDM 3D printing process is widely used to make prototypes and end-use printed parts from affordable polymers like PLA and ABS and, with certain high-level machines, high-performance materials like PEEK.[1]

FFF/FDM has its pros and cons. On the plus side, the layer-by-layer process is quite fast in terms of the total turnaround for a part. This is because no tooling is required; instead, parts can go from digital design to reality within a matter of hours. Extrusion 3D printing is also affordable, with cheap materials, and it can be carried out in non-industrial environments.

On the other hand, the mechanical properties of FFF/FDM parts are inferior to those of parts made by CNC machining and other subtractive manufacturing techniques, and the surface finish is not as good as other plastic 3D printing processes such as SLA.

Recommended reading: An Evolving Industry: 3D Printing Trends and Challenges

FFF vs FDM: What’s the Difference?

There is no conceptual or technological difference between FFF and FDM. The acronym “FDM” is trademarked by Stratasys, and the company retains the sole right to use that name for its products. However, the actual technology described by “FDM” can be built by any manufacturer, just as long as they use a non-trademarked name for it. “FFF” is one such term.

Some websites state that there are other technical features that distinguish FDM from FFF, but this is incorrect. For example, some FFF printers now have enclosed, heated build chambers just like Stratasys machines.

In practice, you will certainly find differences between FDM machines built by Stratasys and FFF machines built by other companies, but these differences are incidental and are not inherent to the definition of either FFF or FDM.

So which term should you use when talking about this type of extrusion 3D printing? In 99% of scenarios, it doesn’t really matter: while you should technically use “FFF” or another generic term when talking about non-Stratasys machines, lots of people have gotten used to the term “FDM” and will use it to describe any filament-extruding printer.

The FDM Patent

Origins

FDM 3D printing was developed by S. Scott Crump, a co-founder of Stratasys, in 1988. Legend has it that Crump’s first print on his prototype FDM printer was a toy frog for his daughter.

A year later, in 1989, Crump and his wife created the company Stratasys, filing a patent for the invention of FDM 3D printing. A patent is a piece of intellectual property for an invention, giving the owner of the patent the exclusive right to build and sell it. In other words, once Stratasys had a patent for FDM 3D printing, nobody else could legally build and sell a 3D printer that worked in a similar way.

The patent was described as “Apparatus and method for creating three-dimensional objects.” Its abstract began like this:

Apparatus incorporating a movable dispensing head provided with a supply of material which solidifies at a predetermined temperature, and a base member, which are moved relative to each other along "X," "Y," and "Z" axes in a predetermined pattern to create three-dimensional objects by building up material discharged from the dispensing head onto the base member at a controlled rate. The apparatus is preferably computer driven in a process utilizing computer aided design (CAD) and computer-aided (CAM) software to generate drive signals for controlled movement of the dispensing head and base member as material is being dispensed.

First printers

Obtaining the patent was not straightforward. In fact, Crump and Stratasys had to wait until 1992 for the patent to be granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).[2] That same year, Stratasys launched its first FDM 3D printer, the 3D Modeler, at a price of $85,000.

Within years, Stratasys — along with stereolithography (SLA) developer 3D Systems — became a leader in rapid prototyping technology. However, prices for its FDM printers remained high: it wasn’t until 1996 that it launched a machine within the $50,000 range.

Expiry

The patent for Crump’s invention lasted for 20 years from its filing date. That meant that in the year 2009, Stratasys no longer had the sole right to make FDM-style 3D printers. This was a watershed moment for 3D printing. In 2009 and the years that followed, a huge number of companies began developing and manufacturing their own extrusion-style 3D printers.

Consumer-oriented desktop 3D printing companies like Makerbot, Ultimaker, and Prusa shot to prominence in this period, selling extrusion-style 3D printers for well under $10,000. Other companies targeted the industrial market, building machines that more closely resembled Stratasys machines.

With so many competitors on the market, Stratasys ultimately had to reduce the prices of many of its FDM machines.

The “FDM” Trademark

The patent for the invention of the FDM 3D printing process expired in 2009. But Stratasys retains, to this day, a trademark for the acronym “FDM.” A trademark is a different type of intellectual property. Whereas a patent applies to an invention, a trademark applies to non-physical things like words, symbols, sounds, and logos that are used to identify products. Stratasys also has several other trademarked names, such as “PolyJet” and “GrabCAD.”

What this means is that other companies can build FDM-style 3D printers, but they cannot legally call these products “FDM” 3D printers. (This can be contrasted with the usage of “SLA”: although 3D Systems founder Chuck Hull invented stereolithography and coined the term, “SLA” is not trademarked and is therefore used by rival companies like Formlabs.)

Here’s where the acronym “FFF” comes in. Standing for “fused filament fabrication,” the term was coined by members of the RepRap open-source community — a network of DIY 3D printer users and developers — in the mid-2000s so they would have a non-trademarked name for this type of technology. Some use the terms “filament freeform fabrication” or “filament extrusion” instead, while some companies use other descriptors and acronyms for their own specific variations of FFF.

In everyday conversation (where there is no threat of litigation from Stratasys) some people might use the term “FDM” to refer to non-Stratasys machines, though this would be technically incorrect.

Differences Between Stratasys FDM printers and Other FFF Printers

Although there is no conceptual difference between FDM and FFF, there are differences between the various Stratasys FDM 3D printers available and the various extrusion-style FFF printers made by other companies. We will examine those differences here.

Size

Since Stratasys remains primarily focused on industrial customers and applications, its FDM printers are large-format machines capable of high throughput. At the extreme end is the Stratasys F900, the company’s best and biggest industrial-grade system, with a build area of 914.4 x 609.6 x 914.4 mm. Few other companies come close to this, though the Roboze ARGO 1000 is slightly bigger.

That being said, Stratasys is now the parent company of hobbyist 3D printer company Makerbot, and the company uses the term “FDM” to describe some small desktop machines like the SKETCH.

Quality

Stratasys is not just the inventor of FDM technology; it is also the market leader with a yearly revenue of more than $600 million.[3] It should be no surprise, therefore, that Stratasys FDM printers (and their associated software) are ahead of most competitors in terms of build quality and reliability.

High-quality machines like the F900 and Fortus 450mc are used by large industrial customers in areas like aerospace and automotive, where quality control is extremely important. Other hardware brands vary greatly in terms of quality: at the lowest end of the quality spectrum are low-cost hobbyist printers that cost a few hundred dollars from platforms like Amazon. Such printers typically have poor print quality.

Print Chamber

Besides the original FDM patent, Stratasys holds and has held other patents related to 3D printing. Between 2000 and 2021, for example, it had a patent for its unique heated print chamber technology.

During this period, other manufacturers were not able to use heated chambers of the sort developed by Stratasys, which made Stratasys FDM printers somewhat unique. However, industrial FFF companies like AON3D and Roboze developed novel solutions so they too could build printers with heated chambers capable of printing high-temperature materials like PEEK.

Today, any competitor building an FFF printer could incorporate a Stratasys-style heated chamber.

Price

Stratasys is a premium company which puts premium prices on its industrial FDM systems. The F900 costs around $200,000, while alternatives from industrial FFF competitors tend to cost less: for example, the leading model from 3DGence costs around $100,000, while the AON3D platform costs around $50,000.

FFF technology, of course, includes both high-end industrial printers like those mentioned above and low-cost, entry-level consumer printers without features like dual extrusion, a heated bed, or a heated chamber.

Recommended reading: The most popular 3D printing materials in FDM and their properties

Other Terms for FFF and FDM

As we have seen, FFF is a generic acronym for extrusion-style 3D printing technology, regardless of the manufacturer, while FDM is a trademarked term for Stratasys 3D printers. However, many other names and acronyms are used to describe the same technology. Below is a non-exhaustive list of such terms.

Term | Acronym | Owner | Notes |

Fused Filament Fabrication | FFF | ||

Filament Freeform Fabrication | FFF | ||

Material Extrusion | MEX | Term also covers 3D printers that use pellets as feedstock instead of filament | |

Fused Deposition Modeling | FDM | Stratasys | Original developer of the technology |

Plastic Jet Printing | PJP | 3D Systems | |

Layer Plastic Deposition | LPD | Zortrax |

Key Takeaways

When looking at the differences between FFF and FDM, the key takeaway is that — from a technology point of view — there are no inherent differences. All FFF/FDM printers use an extrusion mechanism to lay down thermoplastic material in a layer-by-layer fashion.

The important thing to remember is that “FDM” is an acronym trademarked by Stratasys, the inventor of this particular type of 3D printing technology. You should therefore only see “FDM” used to describe industrial Stratasys additive manufacturing systems (and sometimes beginner-friendly machines from New York company Makerbot, which is owned by Stratasys), whereas “FFF” can be freely used by any manufacturer.

Regardless of the term used to describe it, FFF/FDM remains a key 3D printing technology for prototyping and, in some cases, for end-use part production. Most machines now have heated beds as standard, and the range of available materials now goes beyond trusted thermoplastics like PLA, PETG, and TPU, giving users a wide range of possibilities when making plastic parts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is there a difference between FFF and FDM?

In terms of technology, no. The only difference is that "FDM" is trademarked by the 3D printing company Stratasys.

Are there other acronyms to describe this technology as well?

Some companies use their own trademarked names to describe the same (or conceptually similar) technology. Another generic term is "material extrusion" or "MEX," which includes both filament extrusion 3D printers and plastic pellet extrusion 3D printers, which are often used for large-format printing.

Did the FDM patent expire?

The Stratasys patent for FDM 3D printing technology expired in 2009, allowing a number of companies to make their own extrusion 3D printers. However, these other companies cannot use the term "FDM" to describe their products, as the term is still trademarked by Stratasys.

Are FDM 3D printers better than FFF?

Technically, Stratasys is the only company making FDM 3D printers. Its industrial-grade models outperform most FFF machines made by other companies. However, they are some of the most expensive extrusion 3D printers on the market.

References

[1] Garcia-Leiner M, Ghita O, McKay R, Kurtz SM. Additive manufacturing of polyaryletherketones. InPEEK Biomaterials Handbook 2019 Jan 1 (pp. 89-103). William Andrew Publishing.

[2] Pastia C. 3D Printing of Buildings. Limits, Design, Advantages and Disadvantages. Could This Technique Contribute to Sustainability of Future Buildings?. InCritical Thinking in the Sustainable Rehabilitation and Risk Management of the Built Environment: CRIT-RE-BUILT. Proceedings of the International Conference, Iași, Romania, November 7-9, 2019 2020 Oct 29 (p. 298). Springer Nature.

[3] Stratasys [Internet]. 2023 Dec 9. Stratasys Releases Second Quarter 2023 Financial Results [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from: https://investors.stratasys.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/853/stratasys-releases-second-quarter-2023-financial-results