Gantry Systems: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Implementing Gantry Technology

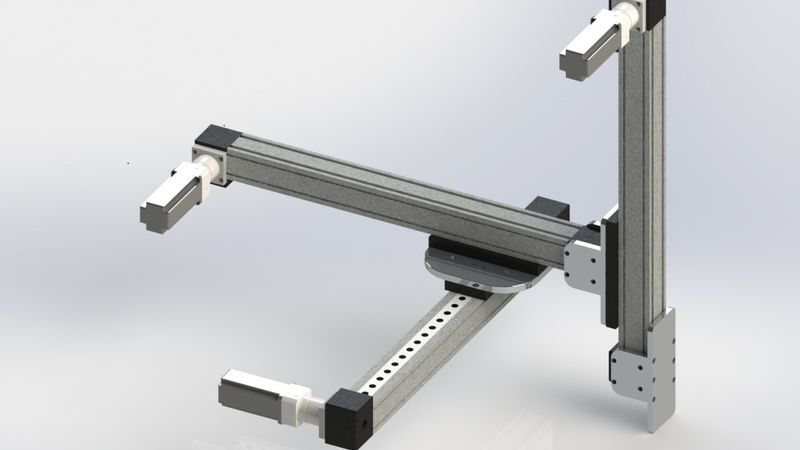

Gantry systems are industrial robots with a mechanical framework that uses a movable trolley over a linear bridge. They have become an indispensable part of various industries due to their unmatched precision, speed, and flexibility.

Key Takeaways

What is a Gantry System: A gantry system is essentially a cartesian robot featuring a multi-axis mechanical framework that moves tools or payloads with high precision over a large work area.

Core Components: Key components include rigid linear rails and frames, bearings or slides for smooth motion, motors and drive mechanisms for movement, and software and hardware control systems.

Types of Gantry Systems: The main architectures are Cartesian Polar and Cylindrical.

Design Considerations: Engineers must consider static and dynamic load capacity, desired speed and precision, rigidity, and environmental factors.

Industry Applications: Gantry robots are used in precision movement applications, heavy equipment handling, general manufacturing and fast, repetitive handling applications.

Introduction

Gantry systems gantry are useful in heavy automation and precision engineering activities such as transporting heavy parts, layer by layer in 3D printing, or even printing in a micrometer range.Blade propelled vehicles, as opposed to robotic arms, enable much more intricate industrial work. Their ability to function within linear, computer controlled, guided settings allows for extreme accuracy, high workspace availability, and significant payload capacity. As such, they are required in a range of industries, from automotive to electronics.

This article explores the theoretical aspects of gantry systems including their core components and mechanics alongside diverse architecture and application. Likewise, design challenges and considerations are described through pragmatic, real-world examples from medical, automotive, semiconductor, and broader manufacturing industries.

Recommended Reading: Robots in the Manufacturing Industry: Types and Applications

Theoretical Concepts of Gantry Systems

Gantry systems are a form of linear robotic platform designed to move objects or tooling in orthogonal directions. They consist of an overhead frame or bridge that spans a work area, with a carriage (or trolley) that traverses along one or more axes. This configuration is essentially a Cartesian coordinate robot that can position a payload at any X-Y-Z coordinate within its working envelope. Because of this design, gantry robots are sometimes simply called Cartesian robots or linear robots.

Role in Automation

Gantry systems provide reliable and repeatable positioning for automated tasks like pick-and-place, assembly, and inspection, reducing human fatigue and enhancing consistency. Their large workspaces and high load capacities enable them to service entire assembly lines, surpassing traditional robotic arms in large-scale operations. They are valued for their speed and precision, making them ideal for broad automation tasks.

Role in Precision Engineering

Gantry systems excel in precision engineering due to their rigid linear motion, achieving micrometer-level accuracy crucial for electronics and semiconductor manufacturing. This accuracy is vital for tasks like CNC machining, 3D printing, and metrology, where precise positioning is paramount for quality and reliability.

Comparison with Articulated Robots

Another theoretical aspect is the difference in kinematics compared to articulated robots. Gantry robots, with their linear axes, offer simpler kinematics compared to 6-axis robotic arms, which have complex rotary joint movements. This results in easier programming and control, especially for straightforward or planar motions. The constrained linear motion of gantries also provides inherent repeatability, reducing errors from flex and backlash.

Suggested Reading: What is a Six Axis Robot: Exploring the Versatile Powerhouse of Industrial Automation

Core Components and Mechanics of Gantry Systems

To understand how gantry systems achieve their performance, let's break down their core components and mechanics. A gantry’s design is modular, comprising several key subsystems that work in concert:

Linear Frame and Rails

Linear rails are the backbone of a gantry robot, providing the tracks along which the moving elements travel. They are typically long, straight tracks made of hardened steel or aluminum, precisely machined to ensure minimal friction and deflection.

Common rail designs include profile rails (rectangular cross-section rails with matching bearing blocks) and round shaft rails.

Profiled linear rails offer high precision and load capacity by using machined tracks and recirculating ball bearings,

Round rails are simpler and often used for lighter loads.

In some gantries, two parallel rails are used for an axis to increase stability (for example, dual X-axis rails supporting a bridge). These rails must be stiff and aligned perfectly straight, as they define the path of motion. Any deviation in the rails would directly translate to positioning errors.

Frame and Gantry Bridge

The frame is the structural framework that holds the rails and other components. Many gantry systems have a bridge or gantry beam that spans between two side supports (like the gantry crane analogy). This bridge carries the Y-axis and Z-axis components.

In a true gantry, both ends of the bridge are supported and move along the X-axis rails. This dual-support design enhances rigidity and allows heavier payloads and longer travel without sagging.

Frames are usually made from steel or aluminum extrusions to provide a stable, vibration-resistant base. The mechanical structure must withstand not only the static weight of payloads but also dynamic forces from acceleration and deceleration.

Bearings and Linear Slides

Mounted on the rails are bearing blocks or linear slides that allow the gantry’s moving parts to glide smoothly. These bearings minimize friction between the stationary rails and the moving carriage. There are a few common types:

Recirculating Ball Bearings: Low-friction, high-precision, and load-bearing; ideal for smooth, accurate motion in precision gantries.

Roller Bearings: High load capacity and stiffness; suitable for heavy-duty applications due to their increased contact area.

Plain Sliding Bearings: Low-cost, robust against dirt, and self-lubricating; used in low-speed, low-precision gantries due to higher friction.

Proper selection of bearings is crucial. The bearing blocks must support not just the payload but also the forces of acceleration (which can be many times the payload weight). They also maintain alignment – poor alignment can cause binding or uneven wear.

Actuators: Motors and Drive Mechanisms

Movement in each axis of a gantry is driven by an actuator. The choice of motor and drive mechanism directly affects the system’s speed, force, and precision.

Stepper Motors: Common in cost-sensitive applications like 3D printers and DIY CNC machines. Stepper motors rotate in discrete steps, enabling open-loop position control. While simple and precise at lower speeds, they can lose synchronization under high loads.

Servo Motors: Used for high-performance gantry systems requiring fast, accurate motion. Paired with encoders and closed-loop controllers, they provide real-time feedback and error correction. These are ideal for industrial robots needing high throughput and precision, especially with variable loads.

Linear Motors: Found in advanced gantry systems, eliminating mechanical transmissions for direct linear motion. They provide smooth motion, high speeds, and exceptional precision due to the absence of backlash. Linear motors are used in high-end applications like semiconductor manufacturing, where extreme accuracy is crucial.

Suggested Reading: Stepper vs Servo Motors: Mastering Motor Selection for Precision Engineering

Drive Mechanics

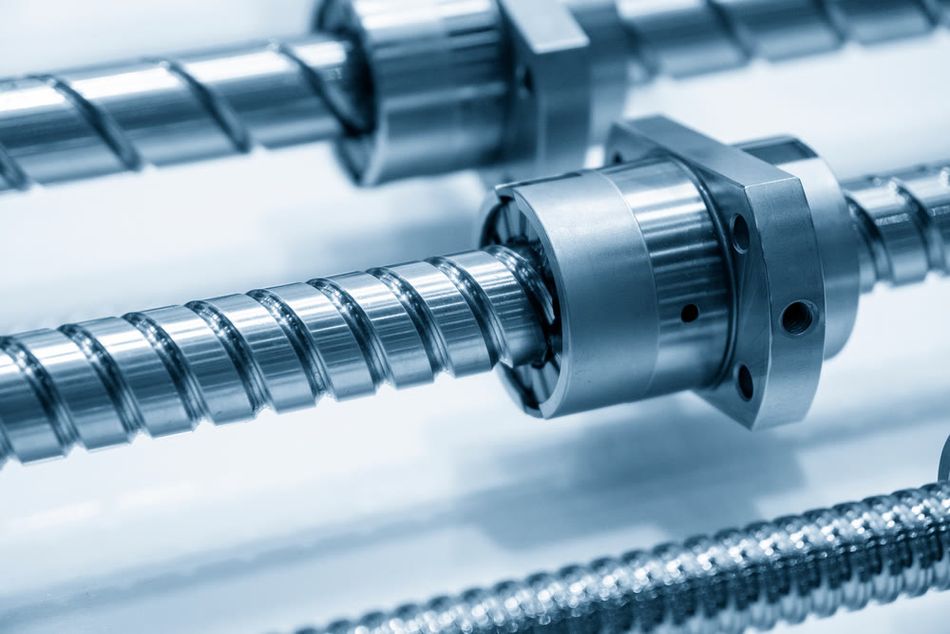

The motor’s rotation usually needs to translate into linear travel. Common mechanisms include:

Ball Screw Drives: Ball screws, driven by a motor, translate rotary motion to linear carriage movement, offering high precision and thrust essential for applications like machine tools. Their minimal backlash, particularly with preloaded nuts, enables micron-level repeatability. However, length constraints to prevent sagging and slower speeds on long axes are limitations.

- Belt Drives: Belt drives, utilizing a motor-driven toothed belt, enable long travel and high speeds, common in packaging and large-area 3D printers, though they offer lower positioning accuracy due to elasticity and are best for light-to-medium loads.

Rack and Pinion Drives: Rack and pinion drives, using a motor-driven pinion engaging a linear rack, handle heavy loads and unlimited lengths, suitable for large CNC routers, offering good precision with high-quality components despite potential backlash.

Control Systems and Software

The “brain” of a gantry system is its control system – typically a motion controller or PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) combined with software that plans and coordinates movement . The control system reads the desired positions and feeds commands to the motors (and monitors feedback from encoders, if present) to execute smooth, coordinated motion along all axes.

Key elements of gantry control include:

Motion Controller / PLC: This hardware coordinates multi-axis movements. In advanced setups, a dedicated motion controller or an industrial PLC with motion control functions calculates the motor trajectories. It ensures that if, for instance, the X and Y axes need to move simultaneously to draw a diagonal line, they do so at the correct relative speeds.

Feedback Sensors: Encoders on motors (or linear scales on axes) provide real-time position feedback to correct any error between the commanded position and actual position. Some gantry systems use high-resolution linear encoders for micron-level precision. For example, a high-end PCB assembly gantry might use linear glass scales to guarantee placement accuracy of components on a circuit board.

Software and Programming: On the software side, gantry systems can be programmed using specialized motion software or G-code. Modern software allows users to plan complex paths, adjust speeds (feeds) and accelerations, and even integrate machine vision or sensors. Features like trajectory planning ensure the gantry moves along smooth curves rather than jerky axis-by-axis motions. The software typically provides a user interface for operators to input parameters, run jobs, and monitor status.

Suggested Reading: What are Articulated Robots? Anatomy, Control Systems, Advantages, Selection Criteria, and Applications

Types of Gantry Systems and Their Applications

The primary types of gantry systems are often classified by the coordinate system they utilize or their geometric arrangement. Here we discuss the three main types – Cartesian, Polar, and Cylindrical gantry systems – along with their characteristics and typical use-cases.

Cartesian Gantry Systems

Cartesian gantry systems excel in applications demanding high precision and repeatability across extensive work areas. Their inherent design, featuring rigid, orthogonally aligned axes, ensures consistent accuracy throughout the entire range of motion. This stiffness, combined with straightforward mechanical components, simplifies maintenance and troubleshooting.

Consequently, Cartesian gantries are the preferred solution for tasks requiring precise linear movements, such as automated assembly, large-format printing, and CNC machining, where maintaining accuracy over a large rectangular or cubic volume is paramount. The modularity of these systems further enhances their appeal, allowing for customization and scalability to meet varying application demands.

Despite their strengths, Cartesian gantries exhibit limitations in certain scenarios. Their rectangular workspace can lead to inefficient utilization of space in non-rectangular layouts, and their linear motion restricts their ability to navigate around obstacles or follow complex, non-linear trajectories.

For applications requiring articulated movement or access to confined spaces, alternative gantry configurations, such as polar or delta systems, may offer superior performance. The larger physical footprint of Cartesian gantries can also be a disadvantage in space-constrained environments. Thus, while highly effective for linear precision tasks, the selection of a gantry system must consider the specific requirements of the application, including workspace geometry and movement complexity.

Advantages of Cartesian Gantries:

High precision across a large rectangular or cubic workspace.

Consistent accuracy due to stiff, guided linear motion.

Simplified maintenance and understanding due to straightforward mechanical design.

Ideal for applications requiring precise linear movement and high repeatability.

Modular design allows for scalability.

Limitations of Cartesian Gantries:

Less efficient for non-linear paths or navigating around obstacles.

Larger footprint, potentially leading to inefficient space utilization (e.g., unused corner space).

Polar Gantry Systems

Polar gantry systems, utilizing a polar coordinate system, employ a rotational base and radial arm to cover a circular or fan-shaped workspace, complemented by a vertical Z-axis. This configuration allows for efficient area coverage, particularly in space-constrained environments where a sweeping motion is required.

By rotating the arm around a central point, a polar gantry can access points within its circular range without the need for extensive linear movements, making it ideal for applications with radial layouts, such as circular assembly lines or round workpieces. This design advantage allows for a smaller footprint relative to the covered area, maximizing space utilization and enabling rapid angular repositioning.

The ability to reach points through rotational motion often results in faster repositioning compared to linear Cartesian systems, especially for angular displacements. Polar gantries excel in scenarios where access to points around a central location is crucial, offering a compact and efficient solution. Their design minimizes the need for large linear movements, streamlining operations and improving throughput in applications where a circular workspace is advantageous.

Suggested Reading: Automotive Robots: Revolutionizing the Assembly Line

Polar Gantry Advantages:

Space-efficient (circular/fan workspace).

Fast rotational movement.

Good access around a center point.

Simplified movement for radial tasks.

Polar Gantry Limitations:

Poor for rectangular tasks.

Complex control for non-radial paths.

Singularity issues at center.

Limited arm reach.

Cylindrical Gantry Systems

Cylindrical gantry systems blend Cartesian and polar characteristics, employing a vertical linear (Z) axis and a rotary axis around a central column, often with a radial extension mechanism. This configuration allows for movement within a cylindrical volume, defined by radius, angle, and height.

The defining feature is the ability to maintain a constant radius during rotation, or vice versa, facilitating unique motion profiles. Some cylindrical gantries feature extending arms for full cylindrical coordinate movement, while others utilize fixed-length arms, covering the surface of a cylinder with a fixed radius. This hybrid design enables access to points within a cylindrical workspace through a combination of linear and rotary motion.

The primary advantages of cylindrical gantries include the ability to maintain a constant tool distance around a circular path, ideal for tasks like drilling around pipes or sensor placement. Their compact footprint, with a centrally located vertical post, is particularly beneficial in space-constrained environments, effectively wrapping the workspace around a pole.

Furthermore, the reduced number of linear axes simplifies mechanical design and reduces weight compared to Cartesian systems, making them a practical solution for specific applications.

Cylindrical Gantry Advantages:

Constant radius movement.

Compact footprint.

Simplified design.

Efficient cylindrical workspace.

Cylindrical Gantry Drawbacks:

Limited Cartesian flexibility.

Reach limitations.

Singularity issues.

Radial extension complexity

Other Notable Gantry Variations

While Cartesian, Polar, and Cylindrical are the classic classifications, it’s worth noting the term gantry is also broadly used. For example, gantry cranes in warehouses are overhead cranes that move along rails – a form of single-axis gantry for heavy lifting. In robotics, sometimes an X-Y gantry with a fixed column is called a “gantry robot” while adding a third axis makes it a full Cartesian robot. There are also gantry hybrids: for instance, an “H-gantry” or “dual drive gantry” where two motors drive the X-axis on either side to avoid racking (common in large 3D printers), or a gantry that carries an articulated robot to combine large workspace with dexterous small movements (some factory setups mount a 6-axis arm on a gantry to get the best of both) .

Gantry Type | Axes & Motion | Workspace Shape | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

Cartesian | X, Y, Z linear axes (orthogonal) | Rectangular prism (box) | CNC machining, 3D printing, pick-and-place, assembly | Simple control and programming; independent linear motions; scalable to large sizes; high precision over area | Large physical footprint for large work areas; not efficient for curved paths; can be heavy for big spans |

Polar | Rotation (θ) + radial extension (r) + vertical (Z) | Circular area (disk or ring) | Painting robots, welding around objects, rotary assembly tables | Covers large area with smaller footprint; can be faster for angular moves; ideal for radial layouts | Complex kinematics; precision varies with angle/radius; harder to move in straight lines; rotary joint backlash can affect accuracy |

Cylindrical | Vertical linear (Z) + rotation around vertical axis (θ) + sometimes radial (r) | Cylindrical volume (tube) | Welding or cutting around pipes, vertical assembly operations, some lab automation | Great for around-the-part operations; maintains constant radius easily; compact vertical design | Coordination of rotary and linear is complex; challenging to keep precision while rotating ; limited reach if no radial axis (fixed arm length) |

Recommended Reading: 8 Different Types of Industrial Robots: A Comprehensive Guide

Design Considerations and Implementation Challenges

Designing a gantry system involves carefully balancing multiple engineering factors to meet the desired performance. A gantry that is fast may sacrifice some precision; one that handles heavy loads might need to be larger or slower. Here are the core design considerations and challenges one must address:

Load Capacity

Load capacity is paramount, considering both static (payload weight) and dynamic (acceleration/deceleration forces) loads. Structural elements and bearings must be sized with a safety margin, using FEA for frame optimization. Modern gantries handle diverse loads, from micro-assembly to heavy material handling, requiring appropriate motor and gearbox selection.

Speed and Precision

Speed and precision often present a trade-off. High-speed gantries face challenges with inertia and vibration, potentially impacting accuracy. Precision involves accuracy and repeatability, with high-end systems achieving micron-level precision. Design considerations include minimizing backlash, using feedback devices, and ensuring structural stability. Engineers often define performance envelopes, balancing speed and precision through control algorithms.

Rigidity and Vibration Damping

Rigidity minimizes flex and resonance, crucial for accuracy. Design techniques include box-section beams, bracing, and dual-rail designs. High-speed gantries may incorporate vibration damping mechanisms like tuned mass dampers. Secure mounting to a stable base is essential, balancing rigidity with weight and cost.

Environmental Factors

Gantries must withstand environmental challenges: temperature variations, humidity, dust, and external vibrations. Temperature changes affect material dimensions, requiring compensation. Dusty environments necessitate protective covers. Cleanrooms demand low-particulate components. External vibrations may require isolation or damping. Cleanliness and maintenance are crucial in medical or food applications.

Control and Integration Challenges

Achieving synchronized multi-axis movement requires precise tuning of motion controllers. Large gantries necessitate synchronized dual drives. Software and PLC logic must handle safety conditions. Integration with other systems, like conveyors and vision systems, demands standard interfaces and real-time networks.

Safety

Safety is critical, with guarding, failsafes, and collision sensors essential. Control systems must prevent crashes and gravity-induced falls. These considerations are vital for practical implementation.

Recommended Reading: Designing Collaborative Robots: Maximizing Productivity and Safety

Examples of Gantry Systems in Industry

Gantry systems have various applications in semiconductor manufacturing, automotive production, medical/laboratory automation, and general manufacturing, highlighting the role gantries play and the benefits they provide in each sector.

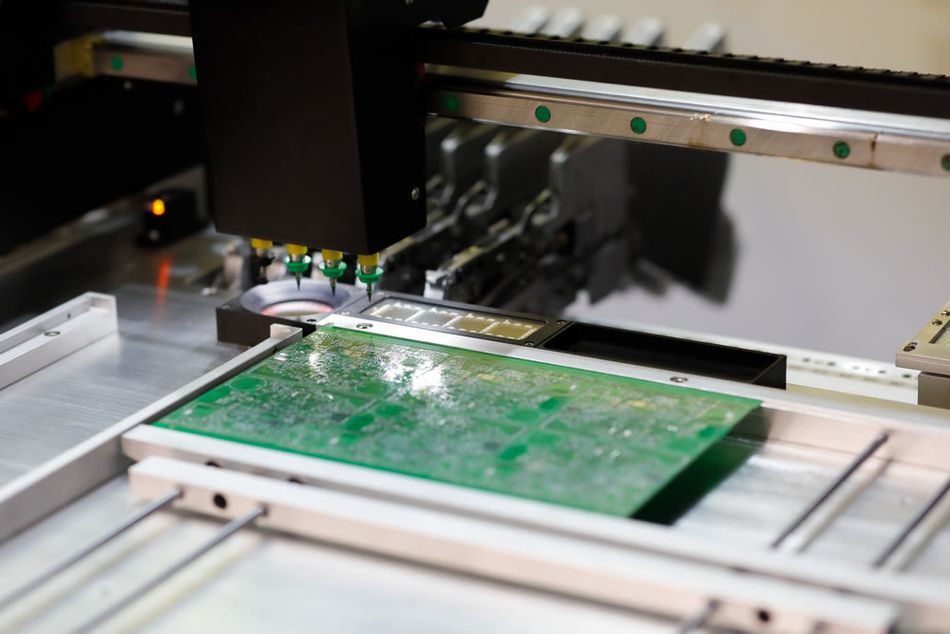

Semiconductor Industry: Micron-Precision Wafer Handling

The semiconductor industry arguably pushes gantry systems to their precision limits. In semiconductor fabrication and assembly, extremely fine positioning is required.

Gantry stages are used in wafer steppers and lithography machines, where silicon wafers must be moved under optics with nanometer-level accuracy. These gantry stages (often X-Y stages) use air bearings and linear motors to achieve ultra-smooth motion, and interferometer feedback to correct position down to fractions of a micron. Even a slight misalignment during photolithography can ruin an entire microchip, so these are among the most precise gantries in the world.

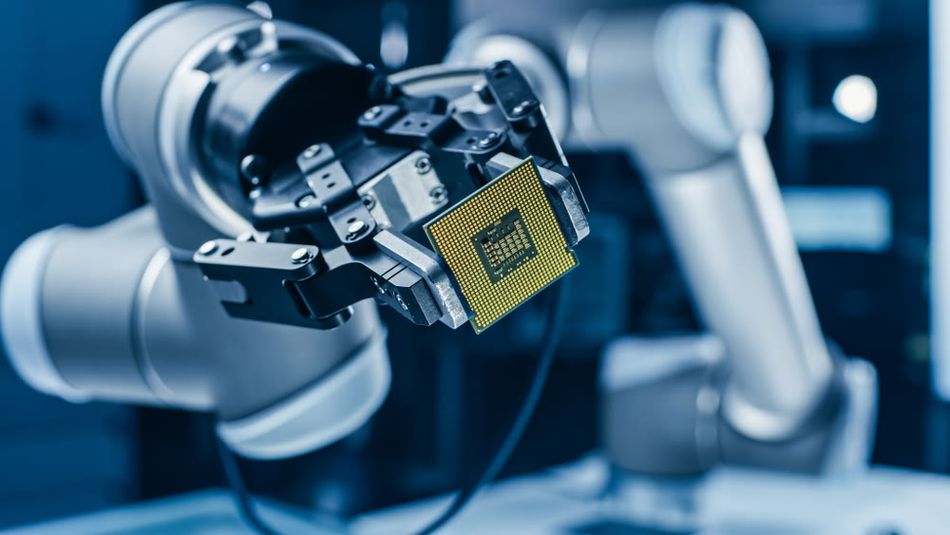

Another use is in pick-and-place of semiconductor chips or packaging. For example, placing tiny silicon dies onto packages or circuit boards requires both precision and gentle handling. Gantry robots equipped with vision systems pick microscopic chips and place them with ±5 µm accuracy or better. The earlier mentioned example of high-resolution encoders achieving ±1 µm accuracy is applicable here – such precision gantries ensure that each chip lands exactly where it should on a wafer or substrate.

Suggested Reading: How are Semiconductors Made? A Comprehensive Guide to Semiconductor Manufacturing

Automotive Industry: Heavy Lifting and Large-Scale Automation

Automotive manufacturing leverages gantry systems for handling heavy components and spanning large areas in assembly lines.

Overhead gantry robots transfer items like engines and windshields, requiring robust designs with powerful servo drives and dual-support rails to manage substantial weights. Material handling gantries, akin to small rooms, move parts racks and load machine tools, offering superior workspace and load capacity compared to articulated robots. Examples include welding car panels and automated warehouse retrieval, emphasizing strength and reliability over micron-level precision.

A significant trend involves integrating gantry and articulated robots, where a six-axis robot is mounted on a gantry for tasks like car painting. This hybrid approach combines the gantry's reach and payload capacity with the articulated robot's dexterity, enabling nuanced motion for complex tasks. Automotive gantries prioritize reliability in harsh environments, incorporating features like automatic lubrication and robust sensors, while also sometimes operating collaboratively alongside human workers.

Suggested Reading: Cobots vs Robots: Understanding the Key Differences and Applications

Medical and Laboratory Automation: Precision and Reliability in Handling

The medical field, including laboratory automation, has seen increasing use of gantry systems for tasks that demand both precision and sterility.

Laboratory automation gantries are essentially small Cartesian robots that handle samples – for example, moving test tubes, pipetting liquids, or sorting lab trays. These gantries might be inside a clinical analyzer machine, carefully dispensing reagents into dozens of samples around the clock.

Important considerations in medical gantries are cleanliness, reliability, and gentle handling. They often use food/medical grade components (stainless steel, special plastics) and are designed to be cleaned easily. In pharmaceutical production, gantry robots might fill vials or move plates in a cleanroom environment, so they must emit low particles and withstand cleaning agents. Also, because human samples or delicate biological materials are involved, the motion must avoid shaking or spilling. Smooth acceleration profiles and fine control are implemented to prevent abrupt motions.

Another area is medical imaging and treatment devices. The term “gantry” is even used in CT scanners and radiation therapy machines, albeit those are rotational gantries (a large ring that rotates around the patient). While not a linear gantry, it shows the broad sense of the word in medicine: a structure that moves equipment (an X-ray source) around a subject. In proton therapy or modern radiotherapy, huge gantries weighing several tons rotate to direct beams at tumors from precise angles – an engineering marvel in its own right, requiring superb rigidity and control to aim beams accurately.

Suggested Reading: Evaluation of AI for medical imaging: A key requirement for clinical translation

General Manufacturing and Assembly: Flexibility and Efficiency

Beyond the specialized sectors above, gantry systems are ubiquitous in general manufacturing. Any process that requires moving something from point A to B in a planar workspace could potentially use a gantry robot. A few examples include:

Pick and Place & Packaging: Packaging factories use gantry robots to place products into containers, sort items, or palletize boxes. For instance, a candy factory might use a high-speed gantry to sort chocolates into assortments. These systems emphasize speed and gentle handling. They might use vacuum grippers on a gantry to pick multiple items at once and drop them into a box in a specific arrangement. Because of the repetitive nature, a gantry’s reliability and speed directly translate to throughput (e.g., X products per minute).

Palletizing: Stacking heavy goods onto pallets can be done by a gantry that moves over a pallet area, placing items in a grid. Automotive and food/beverage industries employ gantry palletizers for cases of products or parts. Gantries are well-suited here because they can span the entire pallet and stack high, something that would require a very large articulated arm otherwise.

Machine Tending: A gantry robot can service multiple CNC machines, loading raw parts and unloading finished parts. The gantry runs above a row of machines, reaching in to pick parts from chucks or fixtures. This maximizes machine utilization and minimizes human intervention in potentially dangerous areas.

Fabrication & Cutting: Plasma cutting tables or laser cutters sometimes use gantry systems to move the cutting head precisely over large sheets of metal. Similarly, large-format 2D printers (billboards, textiles) use gantry motion for the print heads. These require precise tracking over sometimes several-meter spans, which gantries handle well.

Agriculture Automation: Even in agriculture, gantry systems appear, such as automated gantry systems that move above crops for tasks like pruning, spraying, or harvesting in controlled environment farms. They cover large growing beds by moving on rails much like a Cartesian gantry, ensuring each plant gets attention.

Warehouse Automation: While many warehouses use mobile robots or conveyors, some use gantry-like systems for sorting. For instance, an overhead X-Y gantry with a gripper might pick items from bins and place them into orders. Warehouse automation systems benefit from vision integration and AI to decide pick targets, with the gantry providing the physical motion platform.

Conclusion

Gantry systems stand as a cornerstone of automation, offering a unique blend of precision, speed, and load capacity. From fundamental components to diverse configurations like Cartesian, polar, and cylindrical, they adapt to various industrial demands. Key strengths include large work envelopes without sacrificing accuracy and a balanced design considering load, speed, precision, and environment. Looking ahead, Industry 4.0 integration with sensors and AI will enhance gantry capabilities, enabling self-optimization and coordination with other robots. Pre-engineered modules and advanced technologies like composite materials and direct-drive systems will further improve performance and ease of deployment.

Understanding gantry systems is crucial for engineers, as they exemplify mechatronic design principles. Their prevalence in industrial automation and potential for future advancements, including integration with machine vision and articulated robots, underscores their significance. As automation expands into e-commerce and pharmaceuticals, gantries will play a vital role in handling tasks with precision and reliability. Mastering gantry design and programming empowers engineers to create efficient, reliable, and precise solutions, ensuring these systems continue to drive innovation in automation.

FAQ

What is a gantry system in simple terms?

A gantry system is a mechanical platform that moves a tool or payload in multiple linear directions (typically X, Y, and Z). It usually consists of an overhead frame with rails and a moving carriage (or robot) that can position itself anywhere within a defined area. In essence, it’s like a bridge crane or plotter that can precisely carry something to specific coordinates. Gantry systems are often called Cartesian robots because they operate on the Cartesian coordinate system . They are known for high precision and the ability to handle large or heavy items over a big workspace.

What components make up a gantry system?

A gantry system is composed of a few key components:

Frame and Linear Rails: The rigid structure and tracks that define the paths of motion . The rails guide the moving parts in straight lines.

Bearings/Slides: These are the interfaces between moving carriages and rails, allowing smooth, low-friction movement (e.g., ball bearing slides or linear guides) .

Motors and Drive Mechanisms: Motors (stepper or servo) provide motion, usually through drive systems like ball screws, belts, or rack-and-pinion to convert rotation to linear travel. They control how fast and accurately the axes move.

Control System: This includes controllers (PLC or motion controller), drivers for the motors, and software/firmware. The control system coordinates multi-axis movement and takes care of precision, using feedback from encoders or sensors.

End Effector (Tool): Although not part of the gantry itself, the tool attached (gripper, welder, dispenser, etc.) is what the gantry moves around to perform work. The design may include tool changers or mounts for these.

3. In which industries are gantry systems commonly used?

Gantry systems are used in many industries wherever precise and automated motion is needed across a large area. Some examples:

Manufacturing & Assembly: Automated assembly lines, material handling, packaging, and palletizing tasks . Gantries pick and place parts, or load and unload machines.

Automotive: Handling heavy components like engines or car bodies, welding or painting car parts, and storage systems for parts .

Semiconductor & Electronics: Wafer handling, chip placement, PCB assembly, and CNC machining of components – requiring very high precision (micron-level) .

Medical & Pharmaceutical: Laboratory automation (sample handling gantries, pipetting robots), automated drug dispensing, and even imaging devices (CT or radiation therapy gantries).

Logistics/Warehousing: Some warehouses use gantry robots for sorting or retrieving items (like an overhead crane that can move boxes in X-Y).

3D Printing and CNC: Most large 3D printers or CNC routers are essentially gantry systems guiding a toolhead to create or cut objects.

Across these industries, gantries provide speed, accuracy, and repeatability, making processes more efficient and often running 24/7 with minimal human intervention .

How precise and fast can gantry systems get?

Gantry systems can be extremely precise and also quite fast – though the exact performance varies by design:

Precision: High-end precision gantries (like those in semiconductor manufacturing or precision machining) can achieve positioning accuracy on the order of a few micrometers or even sub-micron. For example, with high-resolution encoders and feedback control, a gantry can position to about ±1 µm . Repeatability (hitting the same spot consistently) can be even finer, a few micrometers or less, if the system is properly calibrated and stable. On more standard industrial gantries (for assembly or packaging), typical repeatability might be ±0.02–0.1 mm, which is sufficient for those tasks.

Speed: Gantry robots can also move very fast. Some lightweight gantries reach speeds of 1–3 meters per second on linear axes . In practice, many operate in the range of a few hundred mm/s to 1000+ mm/s depending on the task. For instance, a pick-and-place gantry in electronics might move at 1.5 m/s to quickly position parts. There are trade-offs – at extreme speeds, one might sacrifice some precision due to vibrations and need longer to settle at the target position.

Acceleration: Equally important is acceleration, as it determines how quickly the gantry can get up to speed or make small moves. Some precision stages accelerate at 1–2 G (9.8–19.6 m/s²) for tiny moves. Larger gantries may accelerate slower (to avoid shaking heavy loads).

In summary, top-tier gantry systems combine fine accuracy with high speed, but achieving both requires advanced engineering. The majority of industrial gantries are tuned to balance speed and accuracy for the intended application (e.g., a packaging gantry might prioritize speed ~1 m/s with 0.5 mm accuracy, whereas a machining gantry might go slower but hold 0.01 mm accuracy).

Can gantry systems be customized for specific applications?

A: Yes, gantry systems are highly customizable. In fact, many gantry solutions are built or configured specifically for the application’s needs . Customization can involve:

Size and Axes: Adjusting the length of travel on each axis, adding a third or fourth axis (like a second Y or a rotation axis) if needed, or even building very large-scale gantries for big projects (e.g., construction panels or aircraft assembly).

Load and Motor Sizing: Selecting more powerful motors, different drive mechanisms (belt vs screw), or adding gear reduction to handle heavier loads or achieve higher precision.

Precision Level: Upgrading to higher precision components – for example, using linear encoder feedback or premium low-backlash gearboxes for applications that need tighter accuracy.

Materials and Structure: Using specialized materials (like stainless steel for cleanrooms or carbon fiber for lightweight arms) and tailoring the frame design to the space or mounting requirements.

Software/Control Features: Customizing the control algorithms, adding specific sensors (such as vision systems or force sensors), and programming the software for the task (like integrating certain motion profiles or communication protocols to talk with other machines).

- End Effectors and Tooling: Designing the gantry’s end-of-arm tooling to do exactly what’s needed – be it a vacuum gripper that picks oddly shaped objects or a tool changer that swaps between a drill and a camera.

References

Table of Contents

Key TakeawaysIntroductionTheoretical Concepts of Gantry SystemsRole in AutomationRole in Precision EngineeringComparison with Articulated Robots Core Components and Mechanics of Gantry SystemsLinear Frame and RailsFrame and Gantry BridgeBearings and Linear SlidesActuators: Motors and Drive MechanismsDrive Mechanics Control Systems and SoftwareTypes of Gantry Systems and Their ApplicationsCartesian Gantry SystemsPolar Gantry SystemsCylindrical Gantry SystemsOther Notable Gantry VariationsDesign Considerations and Implementation ChallengesLoad CapacitySpeed and PrecisionRigidity and Vibration DampingEnvironmental FactorsControl and Integration ChallengesSafetyExamples of Gantry Systems in IndustrySemiconductor Industry: Micron-Precision Wafer HandlingAutomotive Industry: Heavy Lifting and Large-Scale AutomationMedical and Laboratory Automation: Precision and Reliability in HandlingGeneral Manufacturing and Assembly: Flexibility and EfficiencyConclusionFAQ3. In which industries are gantry systems commonly used? References